KEY FINDINGS

The latest image exposes details hidden until now.

The geometry runs counter to standard comet physics.

Each new frame raises the stakes for planetary defense.

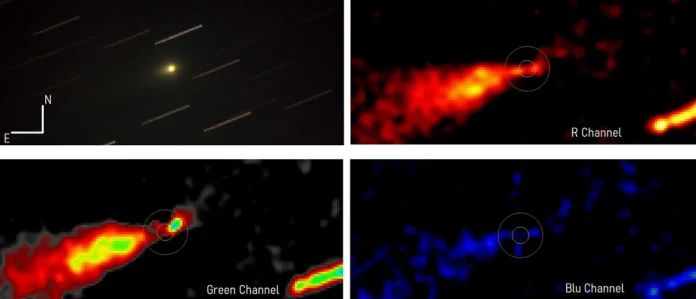

[USA HERALD] – At 1:58 UTC on December 15, 2025, a 0.25-meter telescope in Calabria, Italy, operated by astrophotographer Toni Scarmato, captured one of the most diagnostically important images yet of the interstellar object known as 3I/ATLAS. The raw frame, resolving the object at roughly 1.38 arcseconds per pixel—about 3,850 kilometers at the source distance—shows a compact nucleus embedded in a faint coma. What transforms the observation from routine to consequential, however, is what emerges after multiband processing. When the same data are mapped across red, green, and blue wavelength channels and enhanced using a Larson–Sekanina gradient filter, a single feature dominates the field of view: a narrow, tightly collimated jet extending sunward into a pronounced anti-tail.

In plain terms, that orientation is the problem. Natural comets eject gas and dust that are rapidly swept away from the Sun by radiation pressure and the solar wind, forming tails that stream outward. Anti-tails do exist, but they are typically broad, transient, and governed by the geometry of large dust grains settling into the orbital plane. What appears here is different. Across all three channels—0.658 micrometers in red, 0.53 in green, and 0.445 in blue—the structure is coherent, persistent, and sharply bounded, maintaining its alignment toward the Sun over a span of roughly 1.6 by 0.7 million kilometers. That consistency across wavelengths argues against a processing artifact and points instead to a real, physical emission structure.