KEY FINDINGS

- The modern world runs on satellites, quietly circling Earth and keeping everything from armies to ambulances connected.

- New intelligence assessments shared among Western allies now suggest that this invisible backbone could be deliberately targeted in space.

- If those concerns are justified, the consequences would extend far beyond one company or one conflict zone.

Western intelligence warnings suggest a potential threat to satellite infrastructure that underpins modern warfare, emergency response, and civilian life.

[USA HERALD] – Western intelligence services are raising alarms over a suspected Russian effort to develop an anti-satellite capability that could cripple low-Earth-orbit communications networks, including the Starlink system operated by SpaceX. According to reporting by the Associated Press, officials from two NATO countries have reviewed intelligence suggesting Moscow may be exploring a system designed to disrupt or destroy large numbers of satellites at once.

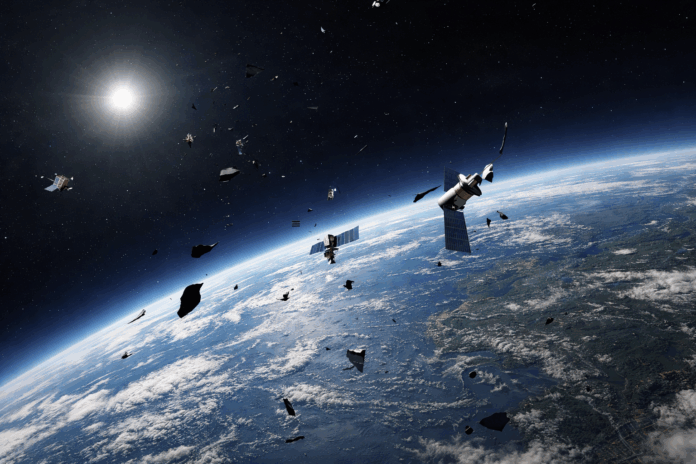

At the center of those concerns is Starlink, the sprawling satellite internet constellation owned by Elon Musk. Starlink consists of thousands of small satellites orbiting relatively close to Earth, providing broadband access across the globe and playing a crucial role in military and civilian communications during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. According to the intelligence assessments summarized by the AP, the suspected Russian concept would involve releasing vast quantities of tiny, dense pellets into orbit, creating clouds of debris capable of striking multiple satellites simultaneously.

Canadian Brig. Gen. Christopher Horner described the theoretical effect in stark terms. Releasing such material, he told the AP, could “blanket an entire orbital regime,” potentially disabling not only Starlink but any spacecraft operating at similar altitudes. While Horner emphasized he has not been formally briefed on a specific deployed system, he said the idea itself was “incredibly troubling” given Russia’s known interest in counter-space weapons.

The stakes are high because satellites are no longer peripheral infrastructure. According to publicly available reporting, Starlink has become essential to Ukraine’s battlefield coordination, emergency communications, and civilian connectivity after repeated attacks on terrestrial networks. More broadly, satellites support global navigation, weather forecasting, financial transactions, disaster response, and routine internet access for remote regions.

Clayton Swope, a space-security analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, explained to the AP that even minuscule debris can have devastating effects in orbit. At orbital velocities, small fragments can puncture solar panels, disable sensors, or knock satellites out of service entirely. Unlike a single missile strike, a debris-based system could leave behind lingering hazards that threaten spacecraft long after any initial attack.

Those dangers would not be limited to commercial systems. Debris generated at Starlink’s operating altitude could slowly drift downward, posing risks to crewed platforms such as China’s Tiangong space station and the International Space Station. The ISS, operated in part by the United States and its allies, relies on constant monitoring and occasional evasive maneuvers to avoid existing space junk. An intentional debris-generating weapon would sharply increase those risks.

The allegations also land amid ongoing scrutiny of Starlink itself. Musk’s satellite network has drawn criticism from astronomers concerned about orbital congestion and light pollution, as well as from regulators and environmental advocates examining the downstream effects of satellite reentries and launch operations. Those debates, however, are distinct from the question now being raised by intelligence officials: whether a nation-state might deliberately weaponize orbital debris to achieve strategic advantage.

Not all experts are convinced the reported Russian concept is either viable or imminent. Victoria Samson, a space-security specialist at the Secure World Foundation, expressed skepticism in comments cited by the AP, saying she does not “buy” the idea as described. Russian officials, for their part, have denied plans to deploy nuclear weapons in space and have publicly called for international limits on space-based arms, though Western governments remain wary of Moscow’s intentions.

Crucially, the intelligence reviewed by the AP does not include a timeline for deployment or confirmation that such a system has been tested. Analysts caution that floating concepts alone can serve strategic purposes, including signaling capability or sowing uncertainty among rivals. International norms, transparency measures, and monitoring regimes currently act as the primary brakes on escalation in space, a domain where misunderstandings could have irreversible consequences.

From a broader perspective, the episode underscores how space has become an extension of terrestrial geopolitics. As more nations and private companies crowd low-Earth orbit, the margin for error shrinks. A single reckless act could trigger cascading effects that render entire orbital bands unusable for decades, harming civilian populations and scientific research as much as military targets.

Whether the reported Russian concept proves real, exaggerated, or purely speculative, the warning itself highlights a fragile reality: modern life depends on orbital systems that remain vulnerable to disruption. The challenge ahead lies not only in defending satellites, but in preserving space as a shared environment where competition does not tip into permanent damage.