Kelly Warner Law Firm Blames USA Herald for Arizona Bar Investigation

In what appears as a desperate attempt to defend multiple allegations of fraud on the courts, the Kelly Warner Law…

By – USA HeraldAaron Kelly Law Firm Resorts To Attacking Former Client Again On KellyWarnerLaw.com – Pattern Recognized

Attorney Aaron Kelly and his law partner Daniel Warner are currently under investigation by the Arizona Bar for legal misconduct.…

By – Jeff WattersonArizona Bar Opens Investigation on Attorney Aaron Kelly

USA Herald recently reported on a developing story involving Attorneys Daniel Warner and Aaron Kelly. Both Warner and Kelly have…

By – Paul O'NealG7 Oil Reserve Release Considered as Iran War Disrupts Global Energy Supply

A sudden shock to the world’s oil arteries has pushed major economies toward an emergency response, with a potential G7…

By – Rihem AkkoucheOpenAI Acquires Promptfoo to Strengthen AI Security and Testing Tools

In a strategic move that underscores the intensifying race to secure advanced artificial intelligence systems, OpenAI acquires Promptfoo, a cybersecurity…

By – Rihem AkkoucheISIS New York Attack Charges Filed After Alleged Bomb Plot at NYC Protest

Federal prosecutors have unveiled ISIS New York attack charges against two young men accused of hurling improvised explosive devices during…

By – Rihem AkkoucheUmbrella Armory filed for Chapter 7 as Gun Industry Slowdown Claims Another Casualty

The cyclical nature of America’s gun market has once again delivered a hard blow. Umbrella Armory filed for Chapter 7,…

By – Rihem AkkoucheIran’s Power Shift: Iran’s Supreme Leader Mojtaba Khamenei Emerges at the Center of Authority

A quiet but consequential shift inside Iran’s ruling establishment has propelled Mojtaba Khamenei into the role of supreme leader, marking…

By – Rihem AkkoucheWhile the World Watches Iran, Gaza Starves

The moment the first US-Israeli strikes hit Iran on February 28, people in Gaza understood what it meant for them.…

By – Rochdi RaisG7 Oil Reserve Release Considered as Iran War Disrupts Global Energy Supply

A sudden shock to the world’s oil arteries has pushed major economies toward an emergency response, with a potential G7…

By – Rihem AkkoucheOpenAI Acquires Promptfoo to Strengthen AI Security and Testing Tools

In a strategic move that underscores the intensifying race to secure advanced artificial intelligence systems, OpenAI acquires Promptfoo, a cybersecurity…

By – Rihem AkkoucheISIS New York Attack Charges Filed After Alleged Bomb Plot at NYC Protest

Federal prosecutors have unveiled ISIS New York attack charges against two young men accused of hurling improvised explosive devices during…

By – Rihem AkkoucheUmbrella Armory filed for Chapter 7 as Gun Industry Slowdown Claims Another Casualty

The cyclical nature of America’s gun market has once again delivered a hard blow. Umbrella Armory filed for Chapter 7,…

By – Rihem AkkoucheIran’s Power Shift: Iran’s Supreme Leader Mojtaba Khamenei Emerges at the Center of Authority

A quiet but consequential shift inside Iran’s ruling establishment has propelled Mojtaba Khamenei into the role of supreme leader, marking…

By – Rihem AkkoucheWhile the World Watches Iran, Gaza Starves

The moment the first US-Israeli strikes hit Iran on February 28, people in Gaza understood what it meant for them.…

By – Rochdi RaisG7 Oil Reserve Release Considered as Iran War Disrupts Global Energy Supply

A sudden shock to the world’s oil arteries has pushed major economies toward an emergency response, with a potential G7…

By – Rihem AkkoucheOpenAI Acquires Promptfoo to Strengthen AI Security and Testing Tools

In a strategic move that underscores the intensifying race to secure advanced artificial intelligence systems, OpenAI acquires Promptfoo, a cybersecurity…

By – Rihem AkkoucheISIS New York Attack Charges Filed After Alleged Bomb Plot at NYC Protest

Federal prosecutors have unveiled ISIS New York attack charges against two young men accused of hurling improvised explosive devices during…

By – Rihem AkkoucheUmbrella Armory filed for Chapter 7 as Gun Industry Slowdown Claims Another Casualty

The cyclical nature of America’s gun market has once again delivered a hard blow. Umbrella Armory filed for Chapter 7,…

By – Rihem AkkoucheIran’s Power Shift: Iran’s Supreme Leader Mojtaba Khamenei Emerges at the Center of Authority

A quiet but consequential shift inside Iran’s ruling establishment has propelled Mojtaba Khamenei into the role of supreme leader, marking…

By – Rihem AkkoucheIPIC Theaters Files for Bankruptcy as Luxury Cinema Chain Seeks Lifeline

The phrase IPIC Theaters files for bankruptcy now marks the latest twist in the turbulent story of America’s movie theater…

By – Rachel MooreThe Northern Lights Return

The Northern Lights have a chance to be visible from several northern U.S. states on Tuesday night, forecasters at the…

By – Jackie AllenFebruary Unemployment Up as Job Losses Surprise Economists

February Unemployment Up as the latest labor market data revealed weaker-than-expected job growth and a slight increase in the national…

By – Jackie AllenLate-Night Attack by Venezuelan National at Florida Beach

A Late-night attack by a Venezuelan National has left a Florida community shaken after authorities say a 26-year-old man ambushed…

By – Jackie AllenTrump’s War in Iran: Congress Confronts Escalation After U.S. Strikes

Trump’s War in Iran was triggered open conflict, casualties, and renewed constitutional debate in Washington. The crisis intensified following reports…

By – Jackie AllenU.S. And Israel Launch Major Strikes On Iran — What It Means For America

TEHRAN, Iran – In a dramatic escalation of global tensions, the United States and Israel launched coordinated military strikes against Iran…

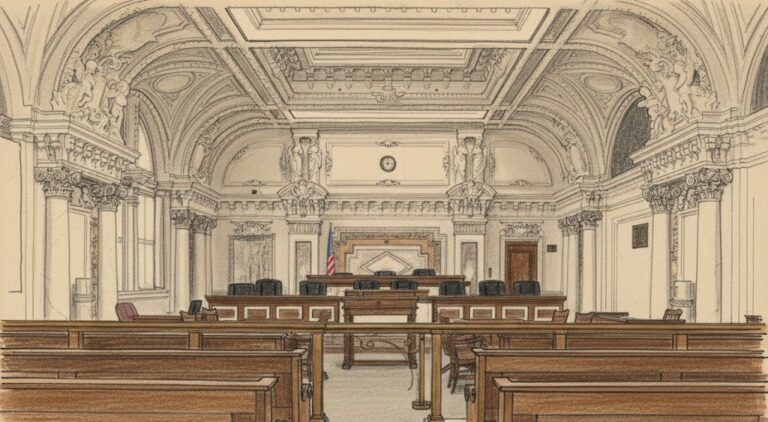

By – Samuel LopezU.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit Overturns $8M Asbestos Verdict Against BNSF Railway Co.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit has thrown out an $8 million jury verdict against BNSF Railway…

By – Tyler BrooksG7 Oil Reserve Release Considered as Iran War Disrupts Global Energy Supply

A sudden shock to the world’s oil arteries has pushed major economies toward an emergency response, with a potential G7…

By – Rihem AkkoucheOpenAI Acquires Promptfoo to Strengthen AI Security and Testing Tools

In a strategic move that underscores the intensifying race to secure advanced artificial intelligence systems, OpenAI acquires Promptfoo, a cybersecurity…

By – Rihem AkkoucheISIS New York Attack Charges Filed After Alleged Bomb Plot at NYC Protest

Federal prosecutors have unveiled ISIS New York attack charges against two young men accused of hurling improvised explosive devices during…

By – Rihem AkkoucheUmbrella Armory filed for Chapter 7 as Gun Industry Slowdown Claims Another Casualty

The cyclical nature of America’s gun market has once again delivered a hard blow. Umbrella Armory filed for Chapter 7,…

By – Rihem AkkoucheIran’s Power Shift: Iran’s Supreme Leader Mojtaba Khamenei Emerges at the Center of Authority

A quiet but consequential shift inside Iran’s ruling establishment has propelled Mojtaba Khamenei into the role of supreme leader, marking…

By – Rihem AkkoucheIPIC Theaters Files for Bankruptcy as Luxury Cinema Chain Seeks Lifeline

The phrase IPIC Theaters files for bankruptcy now marks the latest twist in the turbulent story of America’s movie theater…

By – Rachel MooreWhen The Files Are Finally Unsealed The Most Mind-Bending Truth May Not Be What We Expect

[USA HERALD] – There is a widespread assumption that if governments release their most highly classified files related to unidentified…

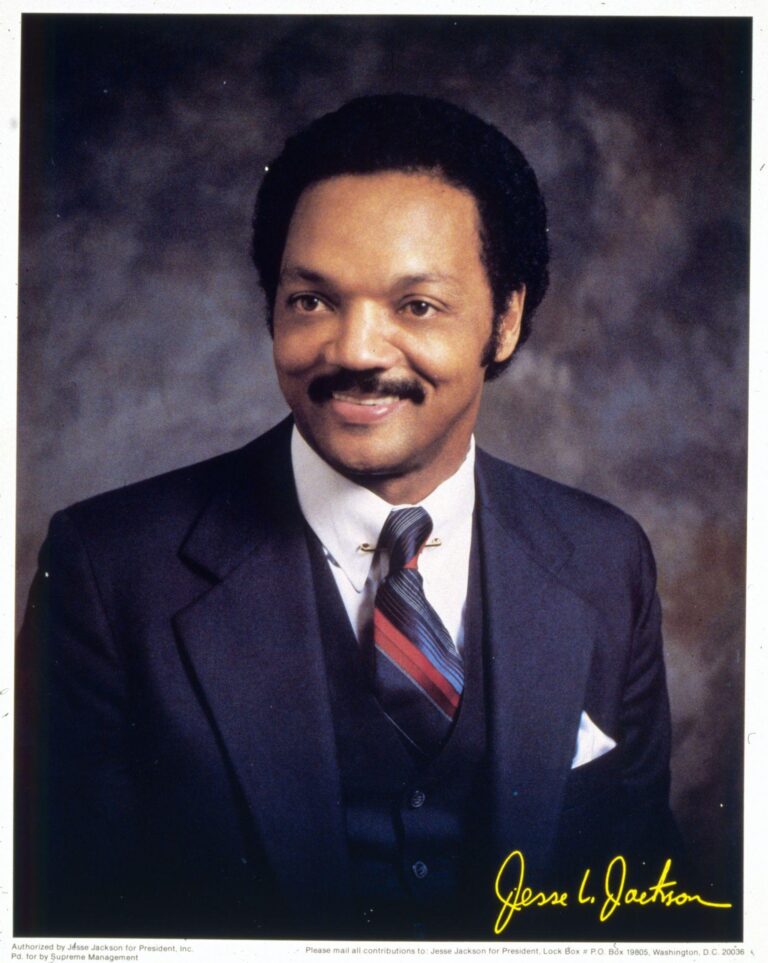

By – Samuel LopezCivil Rights Icon Rev. Jesse Jackson Dies at 84 As President Trump Issues Personal Tribute

[USA HERALD] — The Rev. Jesse Jackson, a towering figure of the American civil rights movement whose career spanned more than…

By – Samuel LopezClues to Savannah Guthrie Missing Mom’s Disappearance Found on Security System

The disappearance of the mother of Savannah Guthrie has taken a dramatic turn as investigators focus on digital clues tied…

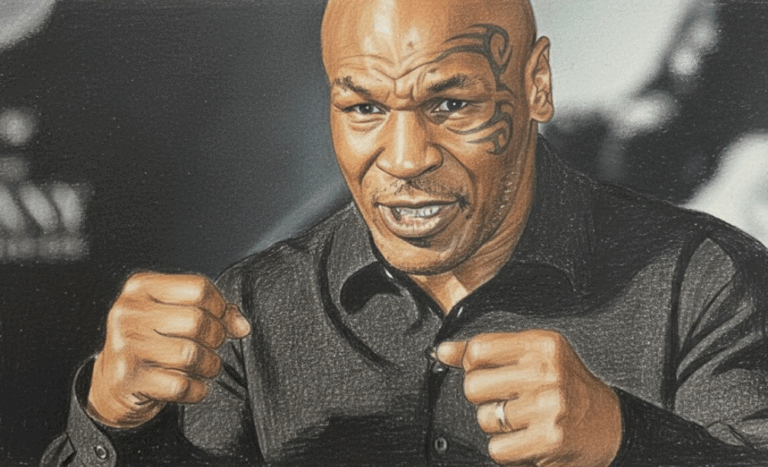

By – Jackie AllenMike Tyson Urges Americans to ‘Eat Real Food’ in Emotional Super Bowl Ad Highlighting Health Risks

Boxing legend Mike Tyson is using his platform ahead of Super Bowl 60 to address a personal and national health…

By – Tyler BrooksDeadly “Death Cap” Mushrooms in California Cause Multiple Deaths and Liver Transplants Amid Rare Super Bloom

California health officials are warning the public after four deaths and three liver transplants linked to the highly toxic death…

By – Ahmed BoughallebFrom Migraines to Miracles: How Becca Valle Survived a Glioblastoma Diagnosis Against the Odds

Becca Valle, 41, thought her headaches were just migraines—until a sudden, unbearable pain revealed something far more serious. In September…

By – Tyler BrooksFebruary Unemployment Up as Job Losses Surprise Economists

February Unemployment Up as the latest labor market data revealed weaker-than-expected job growth and a slight increase in the national…

By – Jackie AllenLate-Night Attack by Venezuelan National at Florida Beach

A Late-night attack by a Venezuelan National has left a Florida community shaken after authorities say a 26-year-old man ambushed…

By – Jackie AllenTrump’s War in Iran: Congress Confronts Escalation After U.S. Strikes

Trump’s War in Iran was triggered open conflict, casualties, and renewed constitutional debate in Washington. The crisis intensified following reports…

By – Jackie AllenCadillac Names Inaugural Formula 1 Car MAC-26 in Tribute to Mario Andretti Ahead of 2026 Australian Grand Prix Debut

Cadillac has officially revealed the name of its first Formula 1 challenger, confirming that its 2026 car will be called…

By – Ahmed BoughallebNorway Tops Medal Table After Day 13 at 2026 Winter Olympics as Team USA Surges Into Second Place

With 13 days complete at the 2026 Milan Cortina Winter Olympics, Norway sits atop the overall medal standings, collecting 34…

By – Ahmed BoughallebOlympic Science Explained: How Figure Skaters Spin at Blinding Speeds Without Getting Dizzy

When Amber Glenn finishes her routine, the arena usually rises with her. The music builds, her blades carve a tight…

By – Tyler BrooksNo posts found.

No posts found.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!