Kelly Warner Law Firm Blames USA Herald for Arizona Bar Investigation

In what appears as a desperate attempt to defend multiple allegations of fraud on the courts, the Kelly Warner Law…

By – USA HeraldAaron Kelly Law Firm Resorts To Attacking Former Client Again On KellyWarnerLaw.com – Pattern Recognized

Attorney Aaron Kelly and his law partner Daniel Warner are currently under investigation by the Arizona Bar for legal misconduct.…

By – Jeff WattersonArizona Bar Opens Investigation on Attorney Aaron Kelly

USA Herald recently reported on a developing story involving Attorneys Daniel Warner and Aaron Kelly. Both Warner and Kelly have…

By – Paul O'NealJohn Gotti’s Grandson Asks Judge for Break, Citing Kidney Donation

The grandson of infamous Gambino crime boss John Gotti is seeking a reduced prison sentence — or at least a…

By – Ahmed BoughallebU.S. Seeks $19M Loan Repayment in Biofuel Fraud Case

Federal prosecutors are pressing a Utah court to compel a businessman to repay more than $19 million tied to a…

By – Tyler BrooksOregon Jury Adds $34M in Latest PacifiCorp Fire Trial

An Oregon jury on Tuesday awarded $34 million in noneconomic damages to 13 plaintiffs in the 16th trial stemming from…

By – Tyler BrooksModerna Reaches $950M Global Settlement To End COVID Vaccine Patent Battle

The biotechnology company Moderna Inc. has agreed to pay at least $950 million to settle global intellectual property litigation involving…

By – Tyler BrooksLive Nation Faces Jury Trial as Antitrust Claims Challenge Ticketing and Venue Practices

Live Nation’s legal team told a Manhattan federal jury that the company operates as a strong competitor in the live…

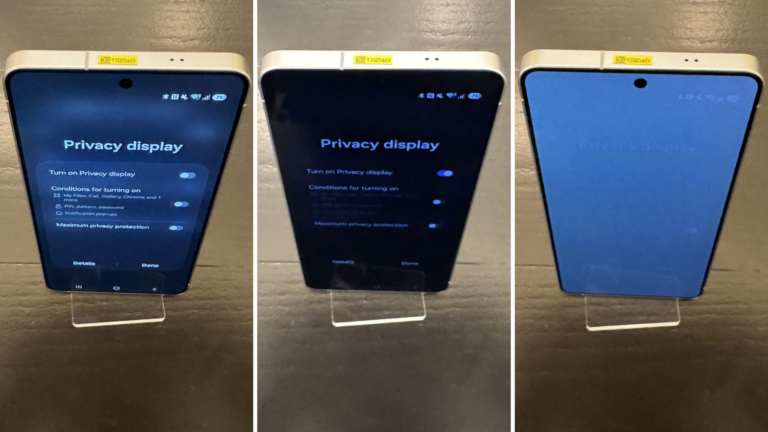

By – Tyler BrooksSamsung Galaxy S26 Ultra Introduces Game-Changing Privacy Display That Puts an End to Shoulder Surfing

At its latest Galaxy Unpacked event, Samsung introduced the new Samsung Galaxy S26 Ultra, positioning it as an “AI phone”…

By – Ahmed BoughallebJohn Gotti’s Grandson Asks Judge for Break, Citing Kidney Donation

The grandson of infamous Gambino crime boss John Gotti is seeking a reduced prison sentence — or at least a…

By – Ahmed BoughallebU.S. Seeks $19M Loan Repayment in Biofuel Fraud Case

Federal prosecutors are pressing a Utah court to compel a businessman to repay more than $19 million tied to a…

By – Tyler BrooksOregon Jury Adds $34M in Latest PacifiCorp Fire Trial

An Oregon jury on Tuesday awarded $34 million in noneconomic damages to 13 plaintiffs in the 16th trial stemming from…

By – Tyler BrooksModerna Reaches $950M Global Settlement To End COVID Vaccine Patent Battle

The biotechnology company Moderna Inc. has agreed to pay at least $950 million to settle global intellectual property litigation involving…

By – Tyler BrooksLive Nation Faces Jury Trial as Antitrust Claims Challenge Ticketing and Venue Practices

Live Nation’s legal team told a Manhattan federal jury that the company operates as a strong competitor in the live…

By – Tyler BrooksSamsung Galaxy S26 Ultra Introduces Game-Changing Privacy Display That Puts an End to Shoulder Surfing

At its latest Galaxy Unpacked event, Samsung introduced the new Samsung Galaxy S26 Ultra, positioning it as an “AI phone”…

By – Ahmed BoughallebJohn Gotti’s Grandson Asks Judge for Break, Citing Kidney Donation

The grandson of infamous Gambino crime boss John Gotti is seeking a reduced prison sentence — or at least a…

By – Ahmed BoughallebU.S. Seeks $19M Loan Repayment in Biofuel Fraud Case

Federal prosecutors are pressing a Utah court to compel a businessman to repay more than $19 million tied to a…

By – Tyler BrooksOregon Jury Adds $34M in Latest PacifiCorp Fire Trial

An Oregon jury on Tuesday awarded $34 million in noneconomic damages to 13 plaintiffs in the 16th trial stemming from…

By – Tyler BrooksModerna Reaches $950M Global Settlement To End COVID Vaccine Patent Battle

The biotechnology company Moderna Inc. has agreed to pay at least $950 million to settle global intellectual property litigation involving…

By – Tyler BrooksLive Nation Faces Jury Trial as Antitrust Claims Challenge Ticketing and Venue Practices

Live Nation’s legal team told a Manhattan federal jury that the company operates as a strong competitor in the live…

By – Tyler BrooksSamsung Galaxy S26 Ultra Introduces Game-Changing Privacy Display That Puts an End to Shoulder Surfing

At its latest Galaxy Unpacked event, Samsung introduced the new Samsung Galaxy S26 Ultra, positioning it as an “AI phone”…

By – Ahmed BoughallebNancy Guthrie Investigation Continues as Person of Interest Released and Home Searched in Rio Rico

Authorities in Arizona are intensifying their search for Nancy Guthrie, 84, the mother of “Today” co-host Savannah Guthrie, who has…

By – Ahmed BoughallebWhat is Aegosexuality?

As conversations around sexuality continue to expand, so does the language we use to describe it. Sexuality terms are gaining…

By – Jackie AllenDonald Trump Responds as Iranian Protesters Gain Ground in Unprecedented Nationwide Uprising

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei is openly blaming Donald Trump as nationwide protests continue to expand and intensify. And Donald…

By – Jackie AllenSavannah Guthrie’s Mom Missing in Arizona: Search Intensifies as FBI Joins Investigation

The desperate search for Savannah Guthrie’s mom continues in Arizona, with authorities entering the fourth day of a widening investigation…

By – Jackie AllenFlaming Star Nebula: A Runaway Star Sets the Cosmos Aglow

Astrophotographer Greg Meyer has unveiled a breathtaking portrait of the Flaming Star Nebula, where the brilliant blue star AE Aurigae…

By – Jackie AllenLinked to China: Google Engineer Linwei Ding Convicted in Landmark AI Espionage Case

A federal jury has convicted former Google software engineer Linwei Ding of stealing a trove of the company’s most sensitive…

By – Jackie AllenJohn Gotti’s Grandson Asks Judge for Break, Citing Kidney Donation

The grandson of infamous Gambino crime boss John Gotti is seeking a reduced prison sentence — or at least a…

By – Ahmed BoughallebU.S. Seeks $19M Loan Repayment in Biofuel Fraud Case

Federal prosecutors are pressing a Utah court to compel a businessman to repay more than $19 million tied to a…

By – Tyler BrooksOregon Jury Adds $34M in Latest PacifiCorp Fire Trial

An Oregon jury on Tuesday awarded $34 million in noneconomic damages to 13 plaintiffs in the 16th trial stemming from…

By – Tyler BrooksModerna Reaches $950M Global Settlement To End COVID Vaccine Patent Battle

The biotechnology company Moderna Inc. has agreed to pay at least $950 million to settle global intellectual property litigation involving…

By – Tyler BrooksLive Nation Faces Jury Trial as Antitrust Claims Challenge Ticketing and Venue Practices

Live Nation’s legal team told a Manhattan federal jury that the company operates as a strong competitor in the live…

By – Tyler BrooksSamsung Galaxy S26 Ultra Introduces Game-Changing Privacy Display That Puts an End to Shoulder Surfing

At its latest Galaxy Unpacked event, Samsung introduced the new Samsung Galaxy S26 Ultra, positioning it as an “AI phone”…

By – Ahmed BoughallebThe Underground Cosmetic Injection Market: Unlicensed “Doctor” Arrested Mid-Procedure in Miami Botox Sting

[FLORIDA] – A Miami woman accused of posing as a doctor while performing cosmetic injections was arrested in the middle…

By – Samuel LopezMike Tyson Urges Americans to ‘Eat Real Food’ in Emotional Super Bowl Ad Highlighting Health Risks

Boxing legend Mike Tyson is using his platform ahead of Super Bowl 60 to address a personal and national health…

By – Tyler BrooksDeadly “Death Cap” Mushrooms in California Cause Multiple Deaths and Liver Transplants Amid Rare Super Bloom

California health officials are warning the public after four deaths and three liver transplants linked to the highly toxic death…

By – Ahmed BoughallebFrom Migraines to Miracles: How Becca Valle Survived a Glioblastoma Diagnosis Against the Odds

Becca Valle, 41, thought her headaches were just migraines—until a sudden, unbearable pain revealed something far more serious. In September…

By – Tyler BrooksNew York Approves Medical Aid in Dying for Terminally Ill Patients

New York Governor Kathy Hochul on Friday signed a law allowing terminally ill residents with less than six months to…

By – Tyler BrooksCalifornia Jury Awards $25 Million to Man Who Developed Lung Disease Linked to PAM Butter-Flavored Cooking Spray

A California civil jury has awarded $25 million to Ronald Esparza after finding Conagra Brands liable for causing his debilitating…

By – Tyler BrooksWhat is Aegosexuality?

As conversations around sexuality continue to expand, so does the language we use to describe it. Sexuality terms are gaining…

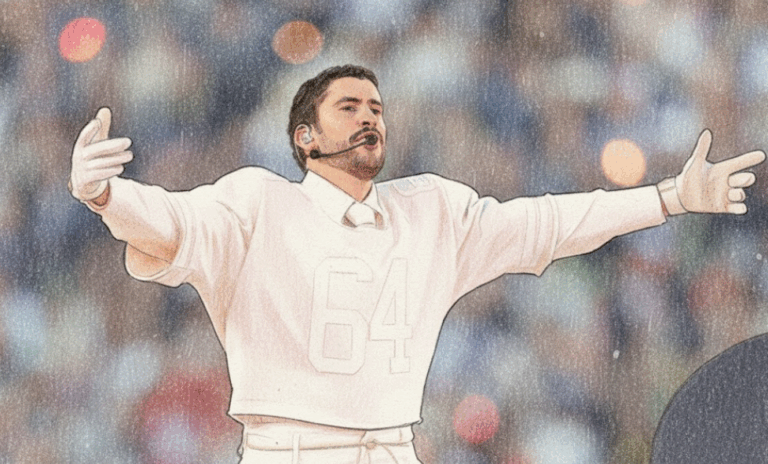

By – Jackie AllenBad Bunny’s Super Bowl Halftime Show Breaks Language Barriers and Ignites Cultural, Political Debate

Bad Bunny’s headlining performance at the Super Bowl 60 halftime show is drawing national attention, with fans and critics debating…

By – Tyler BrooksDonald Trump Responds as Iranian Protesters Gain Ground in Unprecedented Nationwide Uprising

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei is openly blaming Donald Trump as nationwide protests continue to expand and intensify. And Donald…

By – Jackie AllenSavannah Guthrie’s Mom Missing in Arizona: Search Intensifies as FBI Joins Investigation

The desperate search for Savannah Guthrie’s mom continues in Arizona, with authorities entering the fourth day of a widening investigation…

By – Jackie AllenFlaming Star Nebula: A Runaway Star Sets the Cosmos Aglow

Astrophotographer Greg Meyer has unveiled a breathtaking portrait of the Flaming Star Nebula, where the brilliant blue star AE Aurigae…

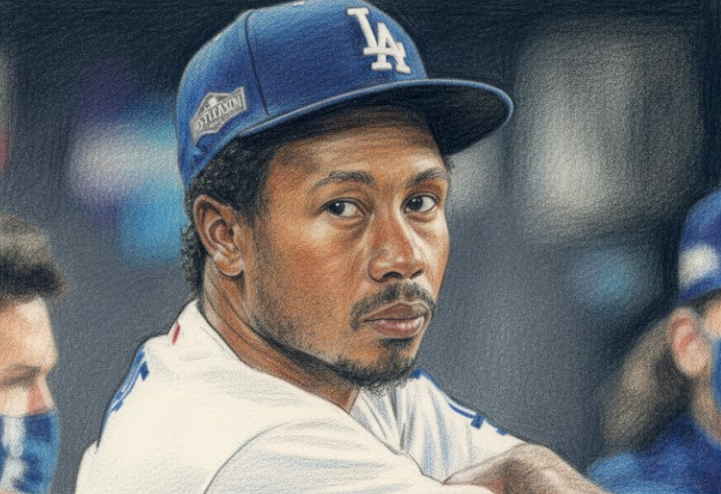

By – Jackie AllenTerrance Gore, Former MLB Star and Three-Time World Series Champion, Passes Away at 34

Terrance Gore, a former Major League Baseball outfielder celebrated for his blazing speed and clutch base running, has died at…

By – Tyler BrooksNo posts found.

No posts found.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!