Kelly Warner Law Firm Blames USA Herald for Arizona Bar Investigation

In what appears as a desperate attempt to defend multiple allegations of fraud on the courts, the Kelly Warner Law…

By – USA HeraldAaron Kelly Law Firm Resorts To Attacking Former Client Again On KellyWarnerLaw.com – Pattern Recognized

Attorney Aaron Kelly and his law partner Daniel Warner are currently under investigation by the Arizona Bar for legal misconduct.…

By – Jeff WattersonArizona Bar Opens Investigation on Attorney Aaron Kelly

USA Herald recently reported on a developing story involving Attorneys Daniel Warner and Aaron Kelly. Both Warner and Kelly have…

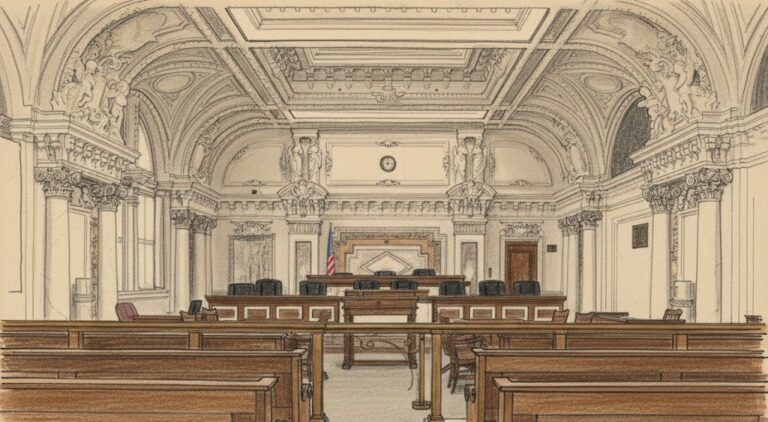

By – Paul O'NealKanye West’s Malibu Mansion Trial Takes Dramatic Turn in Court

The courtroom drama surrounding Kanye West’s Malibu mansion trial took an unusual turn Friday as the artist now legally known…

By – Rihem AkkoucheKuwait Cuts Oil Production as Gulf Tanker Threats Disrupt Global Energy Flow

In a move that underscores the growing shockwaves across global energy markets, Kuwait cuts oil production after tanker traffic through…

By – Rihem AkkoucheOpenAI’s Caitlin Kalinowski Resigns Over Controversial Pentagon AI Agreement

The debate over artificial intelligence and national security intensified this week as OpenAI’s Caitlin Kalinowski resigns, stepping away from her…

By – Rihem AkkoucheTornadoes Damage in Michigan Leaves Multiple Dead as Severe Storms Sweep Across U.S.

Deadly storms carved a destructive path across the Midwest and southern Plains, leaving communities reeling after tornadoes damage in Michigan…

By – Rihem AkkoucheUS Draft AI Chip Sales Rules Could Reshape Global Tech Power Balance

The US draft AI chip sales rules being considered by the administration of Donald Trump could dramatically reshape the global…

By – Rachel MooreSix Flags Amusement Parks Sale Signals Major Shake-Up in Theme Park Industry

A sweeping restructuring is underway in the theme park world as the Six Flags amusement parks sale moves forward, marking…

By – Rachel MooreKanye West’s Malibu Mansion Trial Takes Dramatic Turn in Court

The courtroom drama surrounding Kanye West’s Malibu mansion trial took an unusual turn Friday as the artist now legally known…

By – Rihem AkkoucheKuwait Cuts Oil Production as Gulf Tanker Threats Disrupt Global Energy Flow

In a move that underscores the growing shockwaves across global energy markets, Kuwait cuts oil production after tanker traffic through…

By – Rihem AkkoucheOpenAI’s Caitlin Kalinowski Resigns Over Controversial Pentagon AI Agreement

The debate over artificial intelligence and national security intensified this week as OpenAI’s Caitlin Kalinowski resigns, stepping away from her…

By – Rihem AkkoucheTornadoes Damage in Michigan Leaves Multiple Dead as Severe Storms Sweep Across U.S.

Deadly storms carved a destructive path across the Midwest and southern Plains, leaving communities reeling after tornadoes damage in Michigan…

By – Rihem AkkoucheUS Draft AI Chip Sales Rules Could Reshape Global Tech Power Balance

The US draft AI chip sales rules being considered by the administration of Donald Trump could dramatically reshape the global…

By – Rachel MooreSix Flags Amusement Parks Sale Signals Major Shake-Up in Theme Park Industry

A sweeping restructuring is underway in the theme park world as the Six Flags amusement parks sale moves forward, marking…

By – Rachel MooreKanye West’s Malibu Mansion Trial Takes Dramatic Turn in Court

The courtroom drama surrounding Kanye West’s Malibu mansion trial took an unusual turn Friday as the artist now legally known…

By – Rihem AkkoucheKuwait Cuts Oil Production as Gulf Tanker Threats Disrupt Global Energy Flow

In a move that underscores the growing shockwaves across global energy markets, Kuwait cuts oil production after tanker traffic through…

By – Rihem AkkoucheOpenAI’s Caitlin Kalinowski Resigns Over Controversial Pentagon AI Agreement

The debate over artificial intelligence and national security intensified this week as OpenAI’s Caitlin Kalinowski resigns, stepping away from her…

By – Rihem AkkoucheTornadoes Damage in Michigan Leaves Multiple Dead as Severe Storms Sweep Across U.S.

Deadly storms carved a destructive path across the Midwest and southern Plains, leaving communities reeling after tornadoes damage in Michigan…

By – Rihem AkkoucheUS Draft AI Chip Sales Rules Could Reshape Global Tech Power Balance

The US draft AI chip sales rules being considered by the administration of Donald Trump could dramatically reshape the global…

By – Rachel MooreSix Flags Amusement Parks Sale Signals Major Shake-Up in Theme Park Industry

A sweeping restructuring is underway in the theme park world as the Six Flags amusement parks sale moves forward, marking…

By – Rachel MooreU.S. And Israel Launch Major Strikes On Iran — What It Means For America

TEHRAN, Iran – In a dramatic escalation of global tensions, the United States and Israel launched coordinated military strikes against Iran…

By – Samuel LopezU.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit Overturns $8M Asbestos Verdict Against BNSF Railway Co.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit has thrown out an $8 million jury verdict against BNSF Railway…

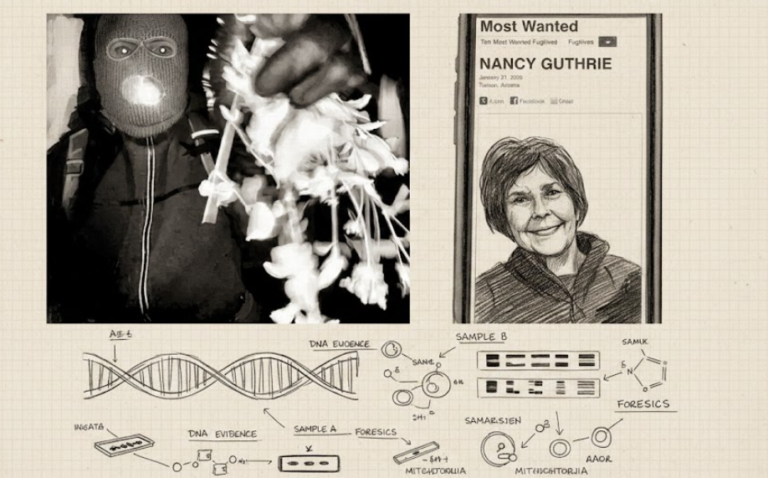

By – Tyler BrooksMissing DNA Evidence May Limit Investigation Into Nancy Guthrie Case, Sources Suggest

Investigators examining DNA recovered from the home of Nancy Guthrie are uncertain whether the biological material will provide enough information…

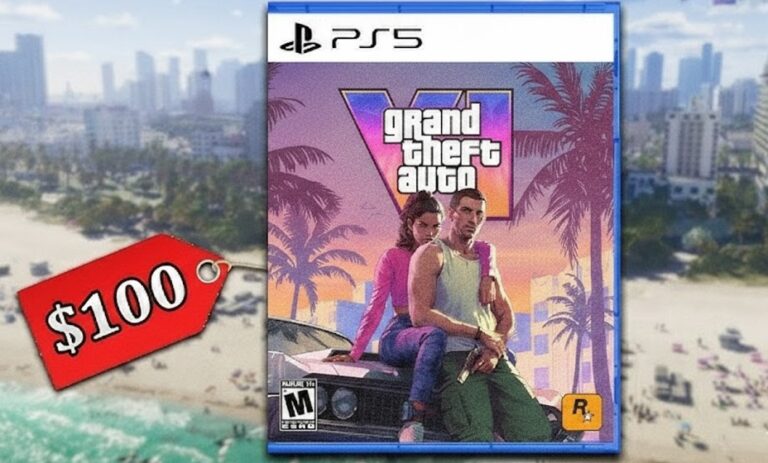

By – Ahmed BoughallebGrand Theft Auto 6 Targets November 2026 Launch as Price Leak Fuels $100 Debate

After years of speculation, teaser trailers and headline-making leaks, Grand Theft Auto VI now has a confirmed global release date:…

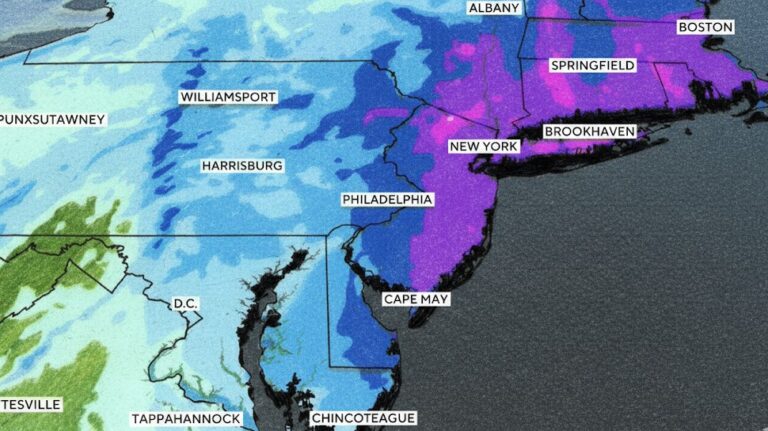

By – Ahmed Boughalleb40 Million Under Blizzard Warnings as Major Winter Storm Threatens U.S. East Coast

More than 40 million people are under blizzard warnings as a powerful winter storm moves across the eastern United States,…

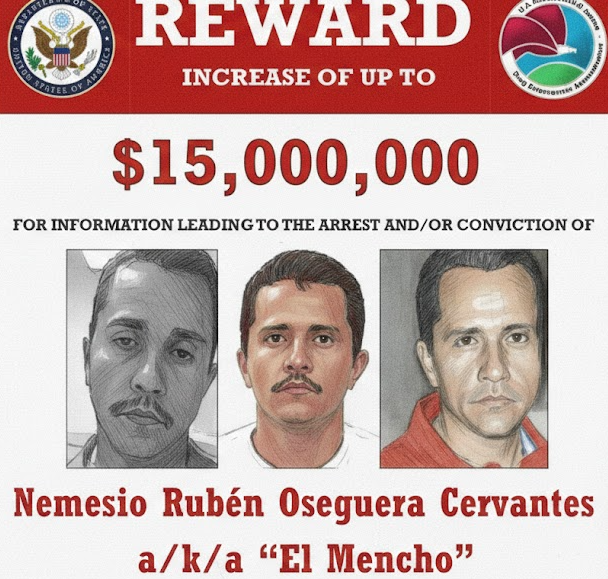

By – Tyler BrooksViolence Erupts Across Mexico After Cartel Leader “El Mencho” Killed in Military Raid, Triggering Roadblocks, Transport Disruptions, and Security Alert Across Several States

Violent clashes spread across western Mexico after security forces killed Nemesio Rubén Oseguera Cervantes, known as “El Mencho,” during a…

By – Ahmed BoughallebKanye West’s Malibu Mansion Trial Takes Dramatic Turn in Court

The courtroom drama surrounding Kanye West’s Malibu mansion trial took an unusual turn Friday as the artist now legally known…

By – Rihem AkkoucheKuwait Cuts Oil Production as Gulf Tanker Threats Disrupt Global Energy Flow

In a move that underscores the growing shockwaves across global energy markets, Kuwait cuts oil production after tanker traffic through…

By – Rihem AkkoucheOpenAI’s Caitlin Kalinowski Resigns Over Controversial Pentagon AI Agreement

The debate over artificial intelligence and national security intensified this week as OpenAI’s Caitlin Kalinowski resigns, stepping away from her…

By – Rihem AkkoucheTornadoes Damage in Michigan Leaves Multiple Dead as Severe Storms Sweep Across U.S.

Deadly storms carved a destructive path across the Midwest and southern Plains, leaving communities reeling after tornadoes damage in Michigan…

By – Rihem AkkoucheUS Draft AI Chip Sales Rules Could Reshape Global Tech Power Balance

The US draft AI chip sales rules being considered by the administration of Donald Trump could dramatically reshape the global…

By – Rachel MooreSix Flags Amusement Parks Sale Signals Major Shake-Up in Theme Park Industry

A sweeping restructuring is underway in the theme park world as the Six Flags amusement parks sale moves forward, marking…

By – Rachel MooreWhen The Files Are Finally Unsealed The Most Mind-Bending Truth May Not Be What We Expect

[USA HERALD] – There is a widespread assumption that if governments release their most highly classified files related to unidentified…

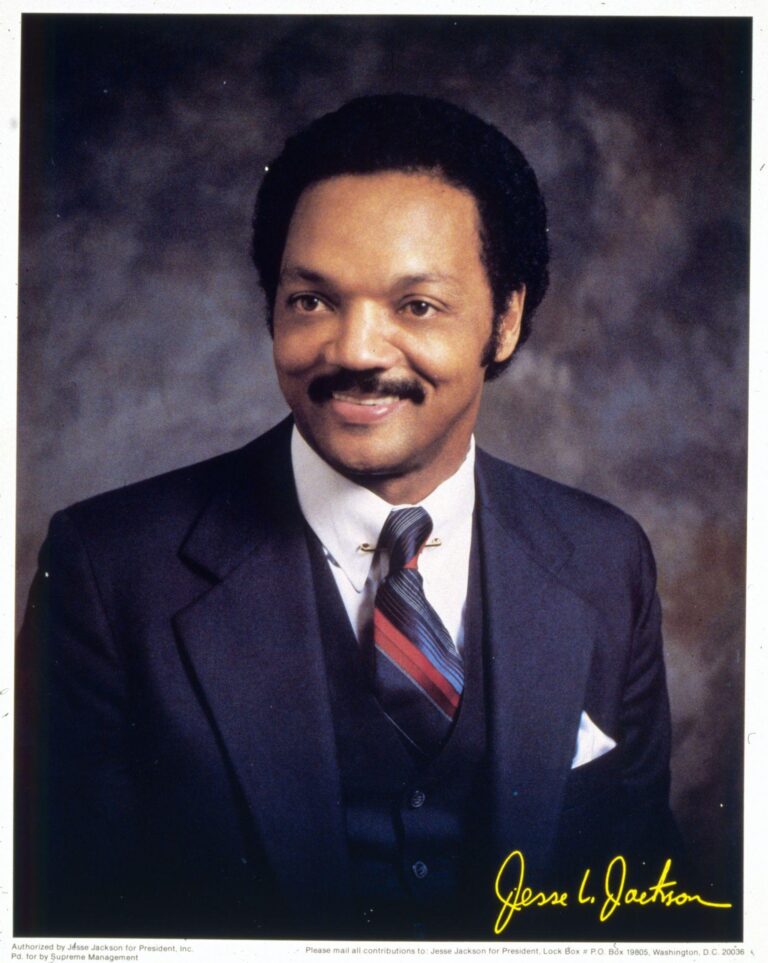

By – Samuel LopezCivil Rights Icon Rev. Jesse Jackson Dies at 84 As President Trump Issues Personal Tribute

[USA HERALD] — The Rev. Jesse Jackson, a towering figure of the American civil rights movement whose career spanned more than…

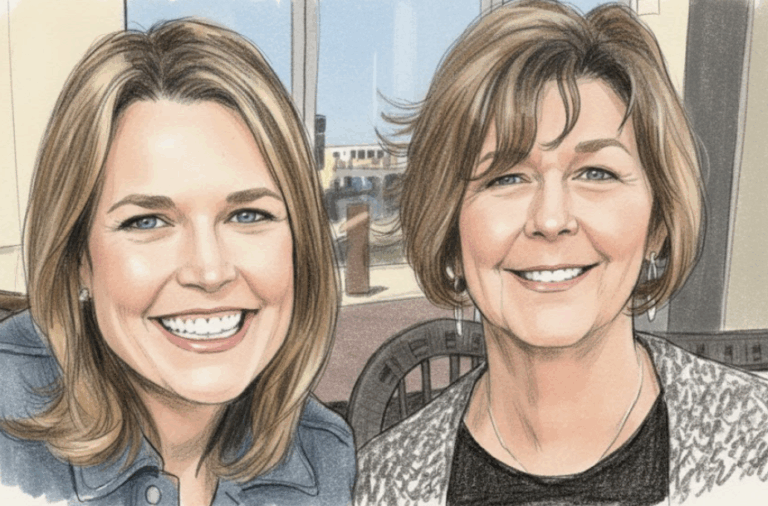

By – Samuel LopezClues to Savannah Guthrie Missing Mom’s Disappearance Found on Security System

The disappearance of the mother of Savannah Guthrie has taken a dramatic turn as investigators focus on digital clues tied…

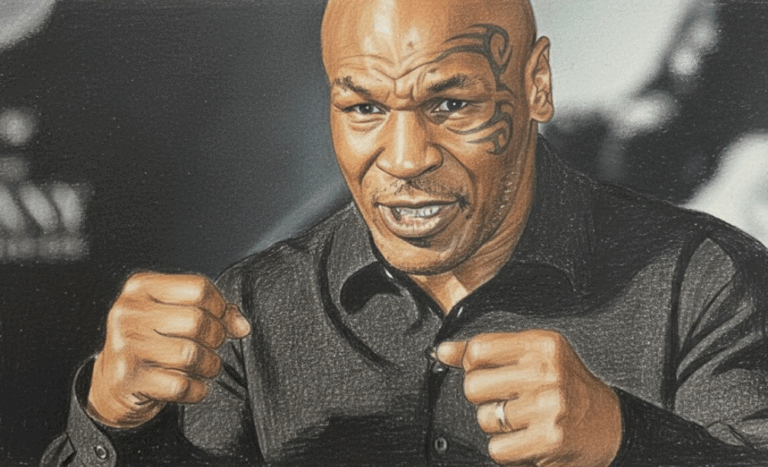

By – Jackie AllenMike Tyson Urges Americans to ‘Eat Real Food’ in Emotional Super Bowl Ad Highlighting Health Risks

Boxing legend Mike Tyson is using his platform ahead of Super Bowl 60 to address a personal and national health…

By – Tyler BrooksDeadly “Death Cap” Mushrooms in California Cause Multiple Deaths and Liver Transplants Amid Rare Super Bloom

California health officials are warning the public after four deaths and three liver transplants linked to the highly toxic death…

By – Ahmed BoughallebFrom Migraines to Miracles: How Becca Valle Survived a Glioblastoma Diagnosis Against the Odds

Becca Valle, 41, thought her headaches were just migraines—until a sudden, unbearable pain revealed something far more serious. In September…

By – Tyler BrooksCadillac Names Inaugural Formula 1 Car MAC-26 in Tribute to Mario Andretti Ahead of 2026 Australian Grand Prix Debut

Cadillac has officially revealed the name of its first Formula 1 challenger, confirming that its 2026 car will be called…

By – Ahmed BoughallebNorway Tops Medal Table After Day 13 at 2026 Winter Olympics as Team USA Surges Into Second Place

With 13 days complete at the 2026 Milan Cortina Winter Olympics, Norway sits atop the overall medal standings, collecting 34…

By – Ahmed BoughallebOlympic Science Explained: How Figure Skaters Spin at Blinding Speeds Without Getting Dizzy

When Amber Glenn finishes her routine, the arena usually rises with her. The music builds, her blades carve a tight…

By – Tyler BrooksOlympic Villages Run Out of Condoms at 2026 Milan-Cortina Games

Condom supplies in the Olympic Villages at the 2026 Winter Games have been temporarily depleted, the Milan-Cortina organizing committee confirmed,…

By – Tyler BrooksArizona Authorities Escalate Search for Savannah Guthrie’s Mom to a Criminal Investigation

In Arizona, police are intensifying their investigation into the disappearance of Nancy Guthrie, Savannah Guthrie’s Mom. The 84-year-old mother of…

By – Jackie AllenWhat is Aegosexuality?

As conversations around sexuality continue to expand, so does the language we use to describe it. Sexuality terms are gaining…

By – Jackie AllenNo posts found.

No posts found.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!