Kelly Warner Law Firm Blames USA Herald for Arizona Bar Investigation

In what appears as a desperate attempt to defend multiple allegations of fraud on the courts, the Kelly Warner Law…

By – USA HeraldAaron Kelly Law Firm Resorts To Attacking Former Client Again On KellyWarnerLaw.com – Pattern Recognized

Attorney Aaron Kelly and his law partner Daniel Warner are currently under investigation by the Arizona Bar for legal misconduct.…

By – Jeff WattersonArizona Bar Opens Investigation on Attorney Aaron Kelly

USA Herald recently reported on a developing story involving Attorneys Daniel Warner and Aaron Kelly. Both Warner and Kelly have…

By – Paul O'NealUS consulate in Dubai struck as drone ignites limited fire

Smoke curled into the Gulf sky Tuesday after the US consulate in Dubai struck by a drone ignited a brief…

By – Rachel MooreChatGPT uninstalls surged by 295% after Pentagon deal backlash

ChatGPT uninstalls surged by 295% on February 28 after news broke that OpenAI had struck a deal with the United…

By – Rachel MooreThe Underground Cosmetic Injection Market: Unlicensed “Doctor” Arrested Mid-Procedure in Miami Botox Sting

[FLORIDA] – A Miami woman accused of posing as a doctor while performing cosmetic injections was arrested in the middle…

By – Samuel LopezSlutty Vegan founder files for bankruptcy amid mounting debts

The entrepreneur behind one of Atlanta’s most talked-about vegan brands — and a new face on reality television — is…

By – Rachel MooreUS considering oil tanker insurance support as Hormuz tensions rattle markets

As missiles arc across the Middle East and oil prices climb like a fever chart, the Trump administration is weighing…

By – Rachel MooreNYC Congestion pricing program will continue after federal court rebuke

A federal judge delivered a sharp blow Tuesday to the Trump administration, ruling that New York City’s landmark congestion toll…

By – Rihem AkkoucheUS consulate in Dubai struck as drone ignites limited fire

Smoke curled into the Gulf sky Tuesday after the US consulate in Dubai struck by a drone ignited a brief…

By – Rachel MooreChatGPT uninstalls surged by 295% after Pentagon deal backlash

ChatGPT uninstalls surged by 295% on February 28 after news broke that OpenAI had struck a deal with the United…

By – Rachel MooreThe Underground Cosmetic Injection Market: Unlicensed “Doctor” Arrested Mid-Procedure in Miami Botox Sting

[FLORIDA] – A Miami woman accused of posing as a doctor while performing cosmetic injections was arrested in the middle…

By – Samuel LopezSlutty Vegan founder files for bankruptcy amid mounting debts

The entrepreneur behind one of Atlanta’s most talked-about vegan brands — and a new face on reality television — is…

By – Rachel MooreUS considering oil tanker insurance support as Hormuz tensions rattle markets

As missiles arc across the Middle East and oil prices climb like a fever chart, the Trump administration is weighing…

By – Rachel MooreNYC Congestion pricing program will continue after federal court rebuke

A federal judge delivered a sharp blow Tuesday to the Trump administration, ruling that New York City’s landmark congestion toll…

By – Rihem AkkoucheUS consulate in Dubai struck as drone ignites limited fire

Smoke curled into the Gulf sky Tuesday after the US consulate in Dubai struck by a drone ignited a brief…

By – Rachel MooreChatGPT uninstalls surged by 295% after Pentagon deal backlash

ChatGPT uninstalls surged by 295% on February 28 after news broke that OpenAI had struck a deal with the United…

By – Rachel MooreSlutty Vegan founder files for bankruptcy amid mounting debts

The entrepreneur behind one of Atlanta’s most talked-about vegan brands — and a new face on reality television — is…

By – Rachel MooreUS considering oil tanker insurance support as Hormuz tensions rattle markets

As missiles arc across the Middle East and oil prices climb like a fever chart, the Trump administration is weighing…

By – Rachel MooreNYC Congestion pricing program will continue after federal court rebuke

A federal judge delivered a sharp blow Tuesday to the Trump administration, ruling that New York City’s landmark congestion toll…

By – Rihem AkkoucheColin Gray Guilty in Georgia School Shooting Case

A Georgia father who gave his teenage son the firearm used in a deadly high school rampage was convicted Tuesday,…

By – Rihem AkkoucheNancy Guthrie Investigation Continues as Person of Interest Released and Home Searched in Rio Rico

Authorities in Arizona are intensifying their search for Nancy Guthrie, 84, the mother of “Today” co-host Savannah Guthrie, who has…

By – Ahmed BoughallebWhat is Aegosexuality?

As conversations around sexuality continue to expand, so does the language we use to describe it. Sexuality terms are gaining…

By – Jackie AllenDonald Trump Responds as Iranian Protesters Gain Ground in Unprecedented Nationwide Uprising

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei is openly blaming Donald Trump as nationwide protests continue to expand and intensify. And Donald…

By – Jackie AllenSavannah Guthrie’s Mom Missing in Arizona: Search Intensifies as FBI Joins Investigation

The desperate search for Savannah Guthrie’s mom continues in Arizona, with authorities entering the fourth day of a widening investigation…

By – Jackie AllenFlaming Star Nebula: A Runaway Star Sets the Cosmos Aglow

Astrophotographer Greg Meyer has unveiled a breathtaking portrait of the Flaming Star Nebula, where the brilliant blue star AE Aurigae…

By – Jackie AllenLinked to China: Google Engineer Linwei Ding Convicted in Landmark AI Espionage Case

A federal jury has convicted former Google software engineer Linwei Ding of stealing a trove of the company’s most sensitive…

By – Jackie AllenUS consulate in Dubai struck as drone ignites limited fire

Smoke curled into the Gulf sky Tuesday after the US consulate in Dubai struck by a drone ignited a brief…

By – Rachel MooreChatGPT uninstalls surged by 295% after Pentagon deal backlash

ChatGPT uninstalls surged by 295% on February 28 after news broke that OpenAI had struck a deal with the United…

By – Rachel MooreThe Underground Cosmetic Injection Market: Unlicensed “Doctor” Arrested Mid-Procedure in Miami Botox Sting

[FLORIDA] – A Miami woman accused of posing as a doctor while performing cosmetic injections was arrested in the middle…

By – Samuel LopezSlutty Vegan founder files for bankruptcy amid mounting debts

The entrepreneur behind one of Atlanta’s most talked-about vegan brands — and a new face on reality television — is…

By – Rachel MooreUS considering oil tanker insurance support as Hormuz tensions rattle markets

As missiles arc across the Middle East and oil prices climb like a fever chart, the Trump administration is weighing…

By – Rachel MooreNYC Congestion pricing program will continue after federal court rebuke

A federal judge delivered a sharp blow Tuesday to the Trump administration, ruling that New York City’s landmark congestion toll…

By – Rihem AkkoucheThe Underground Cosmetic Injection Market: Unlicensed “Doctor” Arrested Mid-Procedure in Miami Botox Sting

[FLORIDA] – A Miami woman accused of posing as a doctor while performing cosmetic injections was arrested in the middle…

By – Samuel LopezMike Tyson Urges Americans to ‘Eat Real Food’ in Emotional Super Bowl Ad Highlighting Health Risks

Boxing legend Mike Tyson is using his platform ahead of Super Bowl 60 to address a personal and national health…

By – Tyler BrooksDeadly “Death Cap” Mushrooms in California Cause Multiple Deaths and Liver Transplants Amid Rare Super Bloom

California health officials are warning the public after four deaths and three liver transplants linked to the highly toxic death…

By – Ahmed BoughallebFrom Migraines to Miracles: How Becca Valle Survived a Glioblastoma Diagnosis Against the Odds

Becca Valle, 41, thought her headaches were just migraines—until a sudden, unbearable pain revealed something far more serious. In September…

By – Tyler BrooksNew York Approves Medical Aid in Dying for Terminally Ill Patients

New York Governor Kathy Hochul on Friday signed a law allowing terminally ill residents with less than six months to…

By – Tyler BrooksCalifornia Jury Awards $25 Million to Man Who Developed Lung Disease Linked to PAM Butter-Flavored Cooking Spray

A California civil jury has awarded $25 million to Ronald Esparza after finding Conagra Brands liable for causing his debilitating…

By – Tyler BrooksWhat is Aegosexuality?

As conversations around sexuality continue to expand, so does the language we use to describe it. Sexuality terms are gaining…

By – Jackie AllenBad Bunny’s Super Bowl Halftime Show Breaks Language Barriers and Ignites Cultural, Political Debate

Bad Bunny’s headlining performance at the Super Bowl 60 halftime show is drawing national attention, with fans and critics debating…

By – Tyler BrooksDonald Trump Responds as Iranian Protesters Gain Ground in Unprecedented Nationwide Uprising

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei is openly blaming Donald Trump as nationwide protests continue to expand and intensify. And Donald…

By – Jackie AllenSavannah Guthrie’s Mom Missing in Arizona: Search Intensifies as FBI Joins Investigation

The desperate search for Savannah Guthrie’s mom continues in Arizona, with authorities entering the fourth day of a widening investigation…

By – Jackie AllenFlaming Star Nebula: A Runaway Star Sets the Cosmos Aglow

Astrophotographer Greg Meyer has unveiled a breathtaking portrait of the Flaming Star Nebula, where the brilliant blue star AE Aurigae…

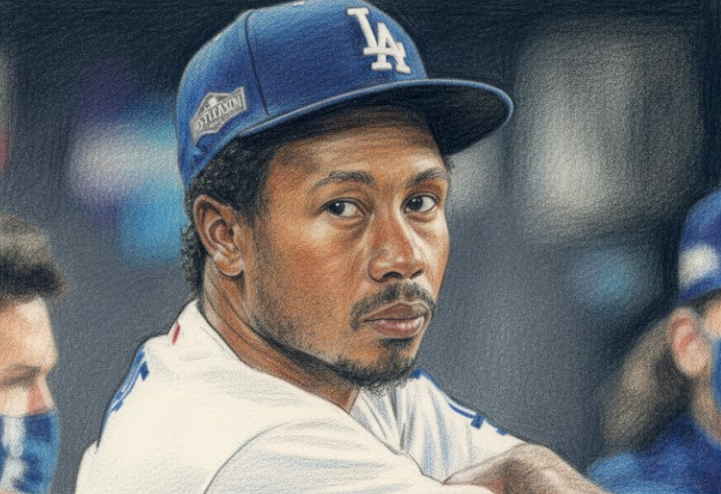

By – Jackie AllenTerrance Gore, Former MLB Star and Three-Time World Series Champion, Passes Away at 34

Terrance Gore, a former Major League Baseball outfielder celebrated for his blazing speed and clutch base running, has died at…

By – Tyler BrooksNo posts found.

No posts found.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!