Kelly Warner Law Firm Blames USA Herald for Arizona Bar Investigation

In what appears as a desperate attempt to defend multiple allegations of fraud on the courts, the Kelly Warner Law…

By – USA HeraldAaron Kelly Law Firm Resorts To Attacking Former Client Again On KellyWarnerLaw.com – Pattern Recognized

Attorney Aaron Kelly and his law partner Daniel Warner are currently under investigation by the Arizona Bar for legal misconduct.…

By – Jeff WattersonArizona Bar Opens Investigation on Attorney Aaron Kelly

USA Herald recently reported on a developing story involving Attorneys Daniel Warner and Aaron Kelly. Both Warner and Kelly have…

By – Paul O'NealSmall Wine Importer Wins Supreme Court Fight Against Trump’s Tariffs — What This Means for Other Businesses

In early 2025, the Liberty Justice Center reached out to Victor Schwartz, a New York City wine importer, with an…

By – Rochdi RaisGun Accessory Manufacturer to Pay $1.75 Million to Buffalo Shooting Victims

A gun accessory company has agreed to pay $1.75 million to survivors and families of victims of the 2022 Buffalo…

By – Tyler BrooksBondi: Ghislaine Maxwell ‘Will Hopefully Die in Prison’ Following Controversial Prison Transfer

During a contentious congressional hearing, the U.S. Attorney General stated that Ghislaine Maxwell “should hopefully die in prison,” sparking renewed…

By – Tyler BrooksFederal Circuit Upholds $85M Antitrust Verdict Against Ingevity for Tying Auto Carbon Filter Patents

The Federal Circuit on Wednesday upheld a Delaware jury’s $85 million antitrust verdict against Ingevity Corp., rejecting the company’s attempt…

By – Tyler BrooksBoeing Seeks to Block LOT’s Late $8.4M Damages Report Ahead of 737 Max Trial

Boeing is seeking to block LOT Polish Airlines from introducing an $8.4 million revised damages report, arguing that the airline…

By – Ahmed BoughallebFederal Circuit Upholds $85M Antitrust Verdict Against Ingevity in Patent Tying Dispute With BASF

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit has affirmed an $85 million antitrust verdict against specialty chemicals company…

By – Tyler BrooksGun Accessory Manufacturer to Pay $1.75 Million to Buffalo Shooting Victims

A gun accessory company has agreed to pay $1.75 million to survivors and families of victims of the 2022 Buffalo…

By – Tyler BrooksBondi: Ghislaine Maxwell ‘Will Hopefully Die in Prison’ Following Controversial Prison Transfer

During a contentious congressional hearing, the U.S. Attorney General stated that Ghislaine Maxwell “should hopefully die in prison,” sparking renewed…

By – Tyler BrooksFederal Circuit Upholds $85M Antitrust Verdict Against Ingevity for Tying Auto Carbon Filter Patents

The Federal Circuit on Wednesday upheld a Delaware jury’s $85 million antitrust verdict against Ingevity Corp., rejecting the company’s attempt…

By – Tyler BrooksBoeing Seeks to Block LOT’s Late $8.4M Damages Report Ahead of 737 Max Trial

Boeing is seeking to block LOT Polish Airlines from introducing an $8.4 million revised damages report, arguing that the airline…

By – Ahmed BoughallebFederal Circuit Upholds $85M Antitrust Verdict Against Ingevity in Patent Tying Dispute With BASF

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit has affirmed an $85 million antitrust verdict against specialty chemicals company…

By – Tyler BrooksAncora Urges Warner Bros. Discovery to Reject Netflix Deal, Backs Paramount’s $30-Per-Share Offer

Ancora Holdings Group has come out against Warner Bros. Discovery’s proposed merger with Netflix, arguing the transaction offers lower value…

By – Ahmed BoughallebGun Accessory Manufacturer to Pay $1.75 Million to Buffalo Shooting Victims

A gun accessory company has agreed to pay $1.75 million to survivors and families of victims of the 2022 Buffalo…

By – Tyler BrooksBondi: Ghislaine Maxwell ‘Will Hopefully Die in Prison’ Following Controversial Prison Transfer

During a contentious congressional hearing, the U.S. Attorney General stated that Ghislaine Maxwell “should hopefully die in prison,” sparking renewed…

By – Tyler BrooksFederal Circuit Upholds $85M Antitrust Verdict Against Ingevity for Tying Auto Carbon Filter Patents

The Federal Circuit on Wednesday upheld a Delaware jury’s $85 million antitrust verdict against Ingevity Corp., rejecting the company’s attempt…

By – Tyler BrooksBoeing Seeks to Block LOT’s Late $8.4M Damages Report Ahead of 737 Max Trial

Boeing is seeking to block LOT Polish Airlines from introducing an $8.4 million revised damages report, arguing that the airline…

By – Ahmed BoughallebFederal Circuit Upholds $85M Antitrust Verdict Against Ingevity in Patent Tying Dispute With BASF

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit has affirmed an $85 million antitrust verdict against specialty chemicals company…

By – Tyler BrooksAncora Urges Warner Bros. Discovery to Reject Netflix Deal, Backs Paramount’s $30-Per-Share Offer

Ancora Holdings Group has come out against Warner Bros. Discovery’s proposed merger with Netflix, arguing the transaction offers lower value…

By – Ahmed BoughallebNancy Guthrie Investigation Continues as Person of Interest Released and Home Searched in Rio Rico

Authorities in Arizona are intensifying their search for Nancy Guthrie, 84, the mother of “Today” co-host Savannah Guthrie, who has…

By – Ahmed BoughallebWhat is Aegosexuality?

As conversations around sexuality continue to expand, so does the language we use to describe it. Sexuality terms are gaining…

By – Jackie AllenDonald Trump Responds as Iranian Protesters Gain Ground in Unprecedented Nationwide Uprising

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei is openly blaming Donald Trump as nationwide protests continue to expand and intensify. And Donald…

By – Jackie AllenSavannah Guthrie’s Mom Missing in Arizona: Search Intensifies as FBI Joins Investigation

The desperate search for Savannah Guthrie’s mom continues in Arizona, with authorities entering the fourth day of a widening investigation…

By – Jackie AllenFlaming Star Nebula: A Runaway Star Sets the Cosmos Aglow

Astrophotographer Greg Meyer has unveiled a breathtaking portrait of the Flaming Star Nebula, where the brilliant blue star AE Aurigae…

By – Jackie AllenLinked to China: Google Engineer Linwei Ding Convicted in Landmark AI Espionage Case

A federal jury has convicted former Google software engineer Linwei Ding of stealing a trove of the company’s most sensitive…

By – Jackie AllenSmall Wine Importer Wins Supreme Court Fight Against Trump’s Tariffs — What This Means for Other Businesses

In early 2025, the Liberty Justice Center reached out to Victor Schwartz, a New York City wine importer, with an…

By – Rochdi RaisAmazon Seeks to Seal Opt-Out Terms in $309M Returns Refund Settlement

Amazon has asked a Seattle federal judge to keep parts of its $309 million settlement over customer return refunds confidential,…

By – Tyler BrooksPaul Weiss, Dechert Lead QXO’s $2.25B Acquisition of Kodiak Building Partners

Building products distributor QXO Inc. has agreed to acquire Kodiak Building Partners from private equity owner Court Square Capital Partners…

By – Tyler BrooksSolv Energy $513M IPO Powers Onto Nasdaq

Power infrastructure heavyweight Solv Energy Inc. surged into public markets Wednesday, completing a Solv Energy $513M IPO that underscores Wall…

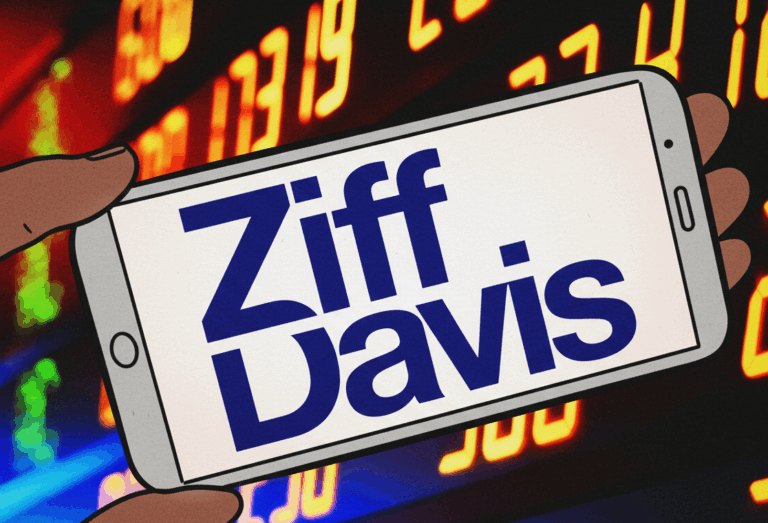

By – Rihem AkkoucheZiff Davis Sues Google Over Alleged Ad-Tech Monopoly

Digital publishing heavyweight Ziff Davis Inc. has launched a sweeping antitrust battle against Google, accusing the tech titan of manipulating…

By – Rihem AkkoucheHome Depot Exec 3 Years Suit Ends in Federal Prison Sentence

A former senior manager who once oversaw real estate tax matters for Home Depot will spend more than three years…

By – Rihem AkkoucheMike Tyson Urges Americans to ‘Eat Real Food’ in Emotional Super Bowl Ad Highlighting Health Risks

Boxing legend Mike Tyson is using his platform ahead of Super Bowl 60 to address a personal and national health…

By – Tyler BrooksDeadly “Death Cap” Mushrooms in California Cause Multiple Deaths and Liver Transplants Amid Rare Super Bloom

California health officials are warning the public after four deaths and three liver transplants linked to the highly toxic death…

By – Ahmed BoughallebFrom Migraines to Miracles: How Becca Valle Survived a Glioblastoma Diagnosis Against the Odds

Becca Valle, 41, thought her headaches were just migraines—until a sudden, unbearable pain revealed something far more serious. In September…

By – Tyler BrooksNew York Approves Medical Aid in Dying for Terminally Ill Patients

New York Governor Kathy Hochul on Friday signed a law allowing terminally ill residents with less than six months to…

By – Tyler BrooksCalifornia Jury Awards $25 Million to Man Who Developed Lung Disease Linked to PAM Butter-Flavored Cooking Spray

A California civil jury has awarded $25 million to Ronald Esparza after finding Conagra Brands liable for causing his debilitating…

By – Tyler BrooksMedtronic Antitrust Lawsuit Update: Jury Weighs $381M Claim in Applied Medical Device Dispute

The legal fight between Medtronic and Applied Medical has entered a critical phase, with jurors now weighing whether the medical…

By – Ahmed BoughallebWhat is Aegosexuality?

As conversations around sexuality continue to expand, so does the language we use to describe it. Sexuality terms are gaining…

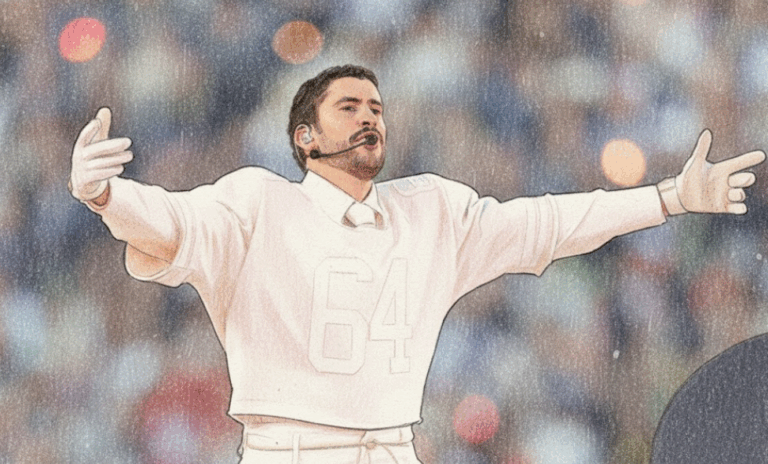

By – Jackie AllenBad Bunny’s Super Bowl Halftime Show Breaks Language Barriers and Ignites Cultural, Political Debate

Bad Bunny’s headlining performance at the Super Bowl 60 halftime show is drawing national attention, with fans and critics debating…

By – Tyler BrooksDonald Trump Responds as Iranian Protesters Gain Ground in Unprecedented Nationwide Uprising

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei is openly blaming Donald Trump as nationwide protests continue to expand and intensify. And Donald…

By – Jackie AllenSavannah Guthrie’s Mom Missing in Arizona: Search Intensifies as FBI Joins Investigation

The desperate search for Savannah Guthrie’s mom continues in Arizona, with authorities entering the fourth day of a widening investigation…

By – Jackie AllenFlaming Star Nebula: A Runaway Star Sets the Cosmos Aglow

Astrophotographer Greg Meyer has unveiled a breathtaking portrait of the Flaming Star Nebula, where the brilliant blue star AE Aurigae…

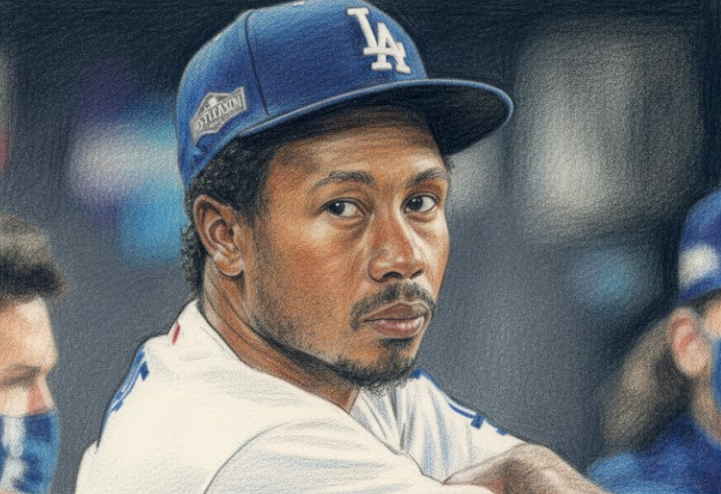

By – Jackie AllenTerrance Gore, Former MLB Star and Three-Time World Series Champion, Passes Away at 34

Terrance Gore, a former Major League Baseball outfielder celebrated for his blazing speed and clutch base running, has died at…

By – Tyler BrooksNo posts found.

No posts found.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!