KEY TAKEAWAYS

The latest images sharpen the trajectory.

The physics grows less predictable near Jupiter.

What happens next could rewrite how interstellar visitors behave.

As an interstellar object barrels toward Jupiter, scientists brace for outcomes that range from spectacular science to total data loss.

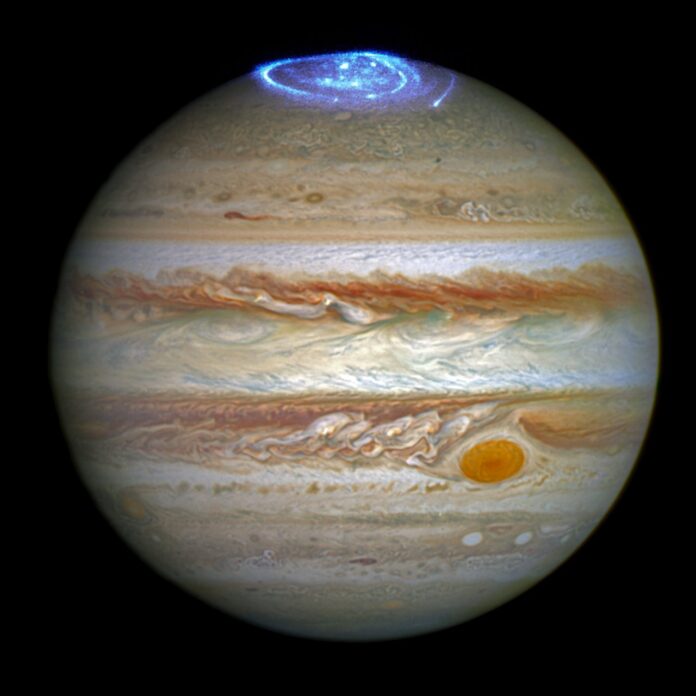

[USA HERALD] – The clock is already running. As interstellar object 3I/ATLAS continues its outbound journey through the solar system, its upcoming close approach to Jupiter has quietly become one of the most consequential—and least forgiving—moments of the entire observation campaign. Jupiter is not just another waypoint. It is a gravitational colossus wrapped in the most violent radiation environment of any planet in the solar system, and when an object already exhibiting anomalous behavior passes close enough to feel Jupiter’s influence, several things can plausibly go wrong—fast.

Based on my review of the most recent ephemeris data, imaging sequences, and prior anomaly patterns, the first and most obvious risk is fragmentation. Jupiter’s tidal forces have a long and documented history of tearing weakly bound objects apart. Comet Shoemaker–Levy 9 is the textbook case, but 3I/ATLAS is not a textbook object. Its rotating jet geometry, unusually persistent anti-tail, and intermittent brightness pulsations suggest a structure that may already be under internal stress. If the nucleus is a loose aggregate rather than a monolithic body, Jupiter’s gravity could induce partial or catastrophic breakup. The danger from a scientific standpoint is not merely destruction, but ambiguity. A fragmented object can instantly obscure whether observed changes are intrinsic to 3I/ATLAS or simply the mechanical aftermath of tidal disruption.

A second plausible failure mode involves rotational destabilization. Months of imaging have shown that 3I/ATLAS’s jet orientation changes faster than standard outgassing models predict. As the object passes through Jupiter’s deep gravitational gradient, even a small torque applied at the wrong moment could accelerate its spin beyond structural limits. In plain terms, the object could begin to shed material uncontrollably, producing a sudden coma expansion or multiple jets that overwhelm instruments and complicate interpretation. From a forensic standpoint, this is where clean cause-and-effect breaks down. Once spin-state chaos sets in, reconstructing what happened—and why—becomes exponentially harder.

The third risk is environmental, not structural. Jupiter’s magnetosphere is immense, extending millions of kilometers into space and filled with charged particles moving at extreme energies. If 3I/ATLAS passes through regions of intense plasma interaction, its dust and gas emissions could behave in ways never observed around the Sun. Jets may appear to switch on or off, not because of internal activity, but because external electromagnetic forces are altering how material is stripped away. This matters because it could mimic or mask propulsion-like effects that some have already mischaracterized in public discourse. Separating intrinsic acceleration from magnetospheric interference will require careful cross-checking across wavelengths and platforms.

There is also the possibility—rare, but nontrivial—that Jupiter’s gravity measurably alters 3I/ATLAS’s trajectory in a way that invalidates prior models. Even a small deviation could ripple forward, changing predicted observation geometry for months. In legal-forensic terms, this is the equivalent of a compromised chain of custody. If the object’s post-Jupiter path diverges unexpectedly, claims about earlier non-gravitational acceleration will have to be reassessed against a new baseline, and weak analyses will collapse under scrutiny.

The final and least discussed risk is observational failure. Jupiter is bright. Its radiation belts are hostile. Spacecraft operating nearby must survive conditions that routinely degrade instruments. While NASA does not have a mission dedicated solely to intercepting 3I/ATLAS, the timing places the object within observational reach of assets already in the Jovian system. NASA’s Juno spacecraft, while not designed for small-body imaging, is positioned closer to Jupiter than any mission in history and could provide contextual data on magnetospheric conditions at the time of encounter. Meanwhile, Earth- and space-based observatories coordinated through NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office and Jet Propulsion Laboratory will attempt to capture high-cadence imaging before, during, and after the pass. Whether those observations survive Jupiter’s glare and radiation noise is an open question.

Several researchers have privately acknowledged that this encounter is a stress test not only for 3I/ATLAS, but for our planetary defense and interstellar tracking infrastructure itself. Harvard astrophysicist Avi Loeb has previously emphasized that close planetary encounters can expose internal properties of interstellar objects that would otherwise remain hidden. That exposure, however, comes at the price of control. Once 3I/ATLAS enters Jupiter’s sphere of influence, the solar system—not scientists—dictates the experiment.

What the evidence suggests, but does not yet prove, is that Jupiter may either clarify 3I/ATLAS’s true nature in dramatic fashion or bury critical answers beneath layers of chaos, fragmentation, and interference. The encounter is not simply another milestone. It is a narrowing window where physics, chance, and preparedness collide, and where even a small miscalculation could mean the permanent loss of irreplaceable data.

We will continue monitoring every frame as new data emerges.