Medtronic to Buy Scientia Vascular in $550 Million Neurovascular Deal

In a move poised to reshape the future of stroke treatment technology, Medtronic to buy Scientia Vascular marks a major…

By – Rachel MooreWinklevoss Twins’ Bitcoin Transfer Sparks Market Speculation

A wave of cryptocurrency movement tied to the founders of the Gemini exchange is drawing fresh attention across the digital…

By – Rihem AkkoucheAlabama Man Fatal Shooting Death Sentence Commuted by Governor

In a rare act of clemency that halted an imminent execution, the Alabama man fatal shooting death sentence tied to…

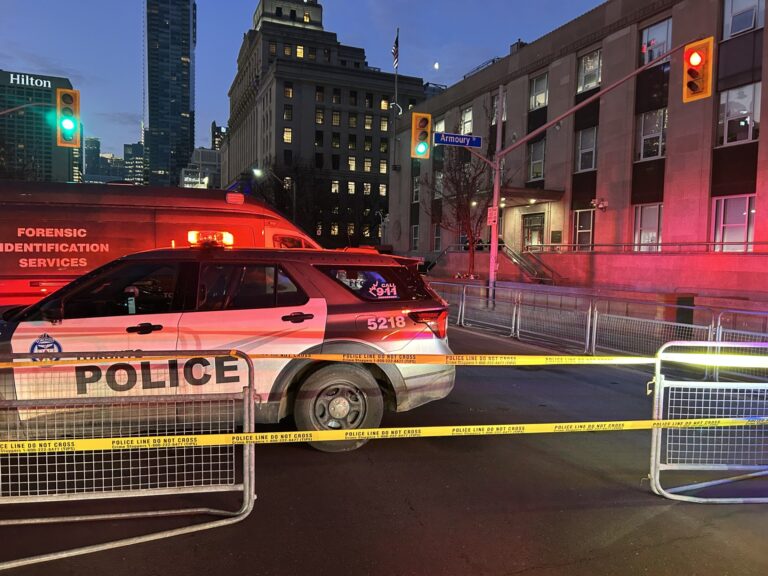

By – Rihem AkkoucheUS Consulate Shooting in Toronto Triggers National Security Investigation

Authorities in Canada are investigating the US consulate shooting in Toronto after gunfire struck the diplomatic building early Monday morning…

By – Rihem AkkoucheExxonMobil to Move to Texas in Historic Corporate Shift

In a move that could reshape the corporate map of one of America’s most powerful energy companies, ExxonMobil to move…

By – Rihem AkkoucheRhoda AI Secures $450M Funding to Power Next-Gen Industrial Robots

In a move set to electrify the robotics industry, Rhoda AI $450M funding marks one of the largest early-stage investments…

By – Rihem AkkoucheRhoda AI Secures $450M Funding to Power Next-Gen Industrial Robots

In a move set to electrify the robotics industry, Rhoda AI $450M funding marks one of the largest early-stage investments…

By – Rihem AkkoucheTrump’s Laser Talk Sparks New Questions About America’s Secret Arsenal

President Donald Trump has once again done what he often does best in moments of war and tension: he dropped…

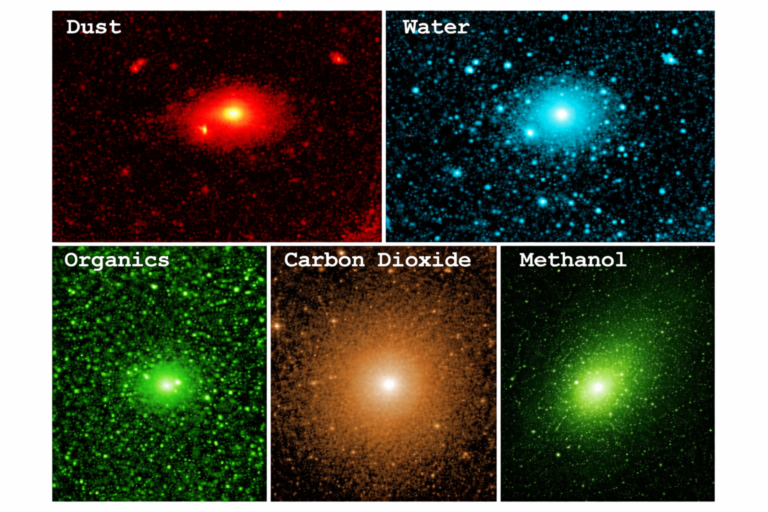

By – Samuel Lopez3I/ATLAS Shocks Astronomers With Fuel-Like Methanol Molecule At Extraordinary Levels

[USA HERALD] – There are ordinary space stories, and then there are the stories that make even seasoned observers stop…

By – Samuel LopezWar Abroad, Risk At Home: Why Americans Are Quietly Reviewing Insurance Policies As Global Conflicts Expand

[USA HERALD] – As the United States confronts rising geopolitical tensions and the possibility of military engagement on multiple fronts…

By – Samuel LopezPentagon-Anthropic AI Dispute Explodes Into Federal Lawsuits Over AI Safety Policies

A fierce clash at the crossroads of technology, national security, and free speech has erupted in Washington, as the Pentagon-Anthropic…

By – Rachel MooreG7 Oil Reserve Release Considered as Iran War Disrupts Global Energy Supply

A sudden shock to the world’s oil arteries has pushed major economies toward an emergency response, with a potential G7…

By – Rihem AkkoucheG7 Oil Reserve Release Considered as Iran War Disrupts Global Energy Supply

A sudden shock to the world’s oil arteries has pushed major economies toward an emergency response, with a potential G7…

By – Rihem AkkoucheOpenAI Acquires Promptfoo to Strengthen AI Security and Testing Tools

In a strategic move that underscores the intensifying race to secure advanced artificial intelligence systems, OpenAI acquires Promptfoo, a cybersecurity…

By – Rihem AkkoucheISIS New York Attack Charges Filed After Alleged Bomb Plot at NYC Protest

Federal prosecutors have unveiled ISIS New York attack charges against two young men accused of hurling improvised explosive devices during…

By – Rihem AkkoucheUmbrella Armory filed for Chapter 7 as Gun Industry Slowdown Claims Another Casualty

The cyclical nature of America’s gun market has once again delivered a hard blow. Umbrella Armory filed for Chapter 7,…

By – Rihem AkkoucheIran’s Power Shift: Iran’s Supreme Leader Mojtaba Khamenei Emerges at the Center of Authority

A quiet but consequential shift inside Iran’s ruling establishment has propelled Mojtaba Khamenei into the role of supreme leader, marking…

By – Rihem AkkoucheIPIC Theaters Files for Bankruptcy as Luxury Cinema Chain Seeks Lifeline

The phrase IPIC Theaters files for bankruptcy now marks the latest twist in the turbulent story of America’s movie theater…

By – Rachel MooreThe Northern Lights Return

The Northern Lights have a chance to be visible from several northern U.S. states on Tuesday night, forecasters at the…

By – Jackie AllenFebruary Unemployment Up as Job Losses Surprise Economists

February Unemployment Up as the latest labor market data revealed weaker-than-expected job growth and a slight increase in the national…

By – Jackie AllenLate-Night Attack by Venezuelan National at Florida Beach

A Late-night attack by a Venezuelan National has left a Florida community shaken after authorities say a 26-year-old man ambushed…

By – Jackie AllenTrump’s War in Iran: Congress Confronts Escalation After U.S. Strikes

Trump’s War in Iran was triggered open conflict, casualties, and renewed constitutional debate in Washington. The crisis intensified following reports…

By – Jackie AllenU.S. And Israel Launch Major Strikes On Iran — What It Means For America

TEHRAN, Iran – In a dramatic escalation of global tensions, the United States and Israel launched coordinated military strikes against Iran…

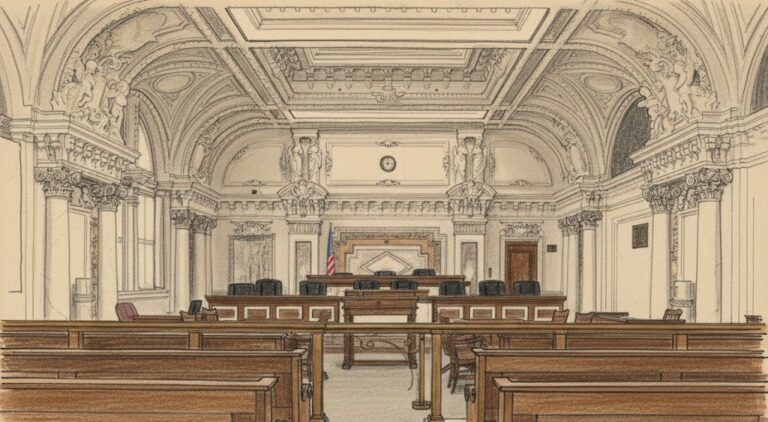

By – Samuel LopezU.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit Overturns $8M Asbestos Verdict Against BNSF Railway Co.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit has thrown out an $8 million jury verdict against BNSF Railway…

By – Tyler BrooksIPIC Theaters Files for Bankruptcy as Luxury Cinema Chain Seeks Lifeline

The phrase IPIC Theaters files for bankruptcy now marks the latest twist in the turbulent story of America’s movie theater…

By – Rachel MooreUS Cuba Economic Deal Emerges as Trump Administration Eyes Major Policy Shift

A potential US Cuba Economic Deal may soon reshape relations between Washington and Havana, according to two sources familiar with…

By – Rachel MooreAmazon FCC Denial of SpaceX Plan Urged in Satellite Showdown

A fierce new battle is unfolding in the race to dominate space-based internet as Amazon FCC denial of SpaceX plan…

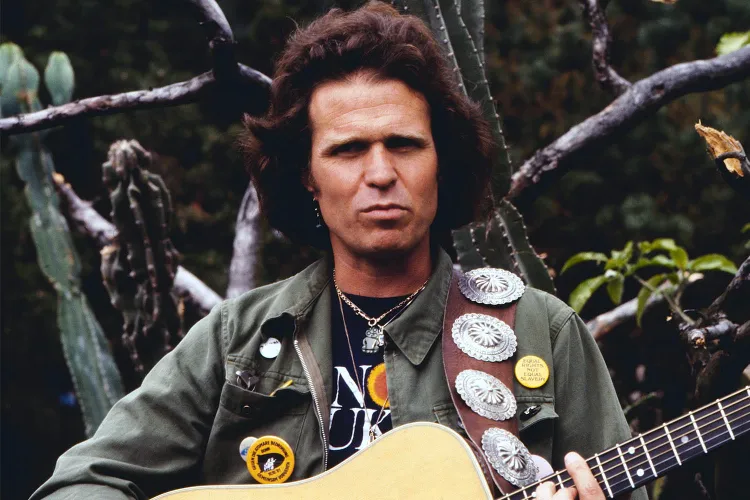

By – Rihem AkkoucheCountry Joe McDonald Died at 84, Woodstock Legend and Protest Voice Falls Silent

The music world is mourning as Country Joe McDonald died at the age of 84, closing the chapter on a…

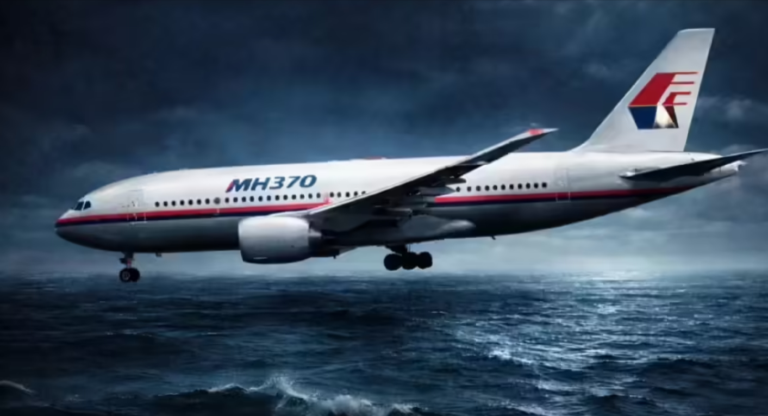

By – Rihem AkkoucheMalaysia Airlines MH370 Disappearance Remains Unsolved After New Ocean Search

More than a decade after one of aviation’s greatest mysteries began, the Malaysia Airlines MH370 disappearance remains unsolved as a…

By – Rihem AkkoucheBlast at US Embassy in Oslo Triggers Terrorism Investigation

An early morning blast at US embassy in Oslo has sparked a sweeping investigation by Norwegian authorities, who say terrorism…

By – Rihem AkkoucheWhen The Files Are Finally Unsealed The Most Mind-Bending Truth May Not Be What We Expect

[USA HERALD] – There is a widespread assumption that if governments release their most highly classified files related to unidentified…

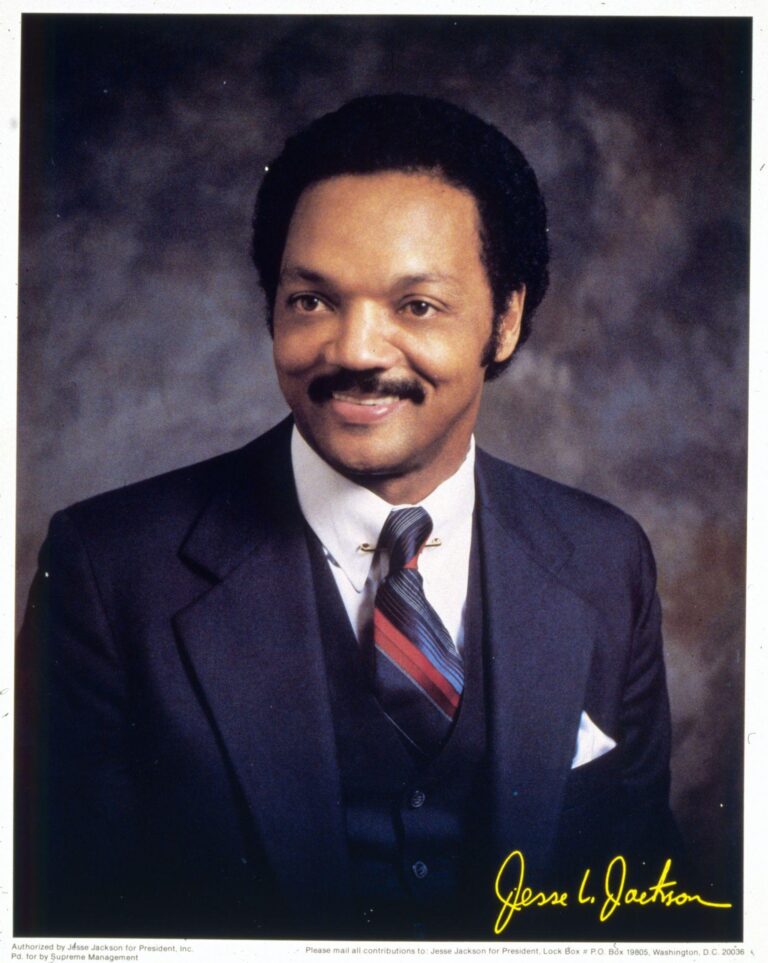

By – Samuel LopezCivil Rights Icon Rev. Jesse Jackson Dies at 84 As President Trump Issues Personal Tribute

[USA HERALD] — The Rev. Jesse Jackson, a towering figure of the American civil rights movement whose career spanned more than…

By – Samuel LopezClues to Savannah Guthrie Missing Mom’s Disappearance Found on Security System

The disappearance of the mother of Savannah Guthrie has taken a dramatic turn as investigators focus on digital clues tied…

By – Jackie AllenMike Tyson Urges Americans to ‘Eat Real Food’ in Emotional Super Bowl Ad Highlighting Health Risks

Boxing legend Mike Tyson is using his platform ahead of Super Bowl 60 to address a personal and national health…

By – Tyler BrooksDeadly “Death Cap” Mushrooms in California Cause Multiple Deaths and Liver Transplants Amid Rare Super Bloom

California health officials are warning the public after four deaths and three liver transplants linked to the highly toxic death…

By – Ahmed BoughallebFrom Migraines to Miracles: How Becca Valle Survived a Glioblastoma Diagnosis Against the Odds

Becca Valle, 41, thought her headaches were just migraines—until a sudden, unbearable pain revealed something far more serious. In September…

By – Tyler BrooksCadillac Names Inaugural Formula 1 Car MAC-26 in Tribute to Mario Andretti Ahead of 2026 Australian Grand Prix Debut

Cadillac has officially revealed the name of its first Formula 1 challenger, confirming that its 2026 car will be called…

By – Ahmed BoughallebNorway Tops Medal Table After Day 13 at 2026 Winter Olympics as Team USA Surges Into Second Place

With 13 days complete at the 2026 Milan Cortina Winter Olympics, Norway sits atop the overall medal standings, collecting 34…

By – Ahmed BoughallebOlympic Science Explained: How Figure Skaters Spin at Blinding Speeds Without Getting Dizzy

When Amber Glenn finishes her routine, the arena usually rises with her. The music builds, her blades carve a tight…

By – Tyler BrooksOlympic Villages Run Out of Condoms at 2026 Milan-Cortina Games

Condom supplies in the Olympic Villages at the 2026 Winter Games have been temporarily depleted, the Milan-Cortina organizing committee confirmed,…

By – Tyler BrooksArizona Authorities Escalate Search for Savannah Guthrie’s Mom to a Criminal Investigation

In Arizona, police are intensifying their investigation into the disappearance of Nancy Guthrie, Savannah Guthrie’s Mom. The 84-year-old mother of…

By – Jackie AllenWhat is Aegosexuality?

As conversations around sexuality continue to expand, so does the language we use to describe it. Sexuality terms are gaining…

By – Jackie AllenNo posts found.

No posts found.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!