KEY FINDINGS

- The shape is unmistakable.

- The symmetry is unnatural.

- And the implications lead directly to December 19.

A new image reveals a feature that challenges the most familiar rules in comet science.

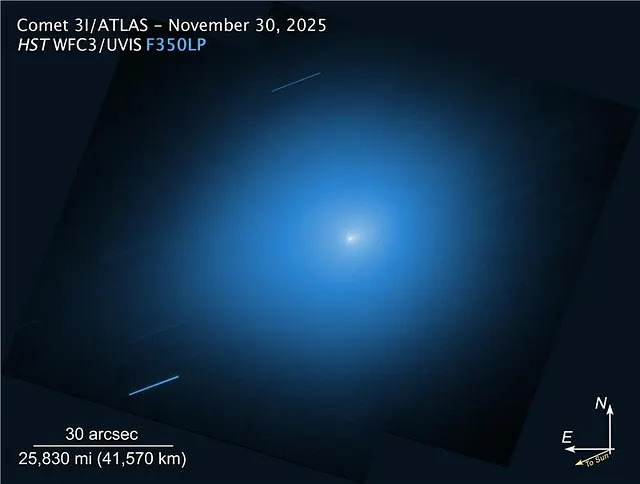

By Samuel Lopez | USA Herald – When NASA and the Space Telescope Science Institute released the newest Hubble image of 3I/ATLAS—taken November 30, 2025 using the F350LP filter aboard the Wide Field Camera 3—I found myself staring not at a comet’s familiar disorder, but at something profoundly structured. A smooth, spherical glow extends outward nearly 40,000 kilometers in all directions, yet from this perfect shell emerges a narrow, elongated extension pointing directly toward the Sun. That single detail, hiding in plain sight, is the anomaly that changes everything.

In the language of comet science, this feature is called an anti-tail—a tail that extends toward the Sun rather than away from it. In the laws of physics, that feature should not exist. And yet here it is, sharper and more defined than ever.

The significance of this becomes clearer when we compare it to natural behavior. Comets shed volatile ices that vaporize under solar heating, producing a dust tail that curves gently backward and an ion tail that stretches straight outward, pushed by the solar wind. Every motion, every plume, every brightening is chaotic. Nothing remains stable. Nothing remains predictable. And nothing, under any standard comet model, organizes into a clean, sunward line of debris tens of thousands of kilometers long. Yet this is exactly what the new Hubble image shows: a 60,000-kilometer sunward extension, narrow, and coherent.

To understand why this matters, it helps to look at the work of Harvard astrophysicist Avi Loeb, who has been studying 3I/ATLAS with growing scientific interest. Loeb suggests that the teardrop-shaped halo is not made of dust or gas at all. Instead, he argues it is composed of macroscopic non-volatile fragments—solid objects, not dust grains—that were separated from the main body during perihelion by the object’s measured non-gravitational acceleration away from the Sun. In plain English, the object sped up in a way that cannot be explained by solar radiation alone, and in the process, it shed solid pieces that remained clustered in a predictable formation.

This is where the story becomes remarkable. Loeb’s model predicted that by November 30—if these large fragments separated from ATLAS at perihelion—they should appear approximately 60,000 kilometers closer to the Sun than the main body. Hubble’s newly released image shows the anti-tail extending almost exactly 60,000 kilometers. In the world of investigative analysis, that degree of alignment between prediction and observation is rare. In astrophysics, it is extraordinary. And in the context of interstellar visitors—objects that arrive without warning and behave in ways our models are not built to anticipate—it is a moment of clarity in the middle of confusion.

The image does more than confirm a prediction. It reveals a pattern. The spherical coma is unusually symmetric for a body that should be venting gas unevenly after perihelion. The nucleus remains compact and stable in appearance. The star streaks across the image—straight white lines produced by Hubble’s tracking of ATLAS—remind us that the object’s motion is smooth and steady, not jittered by chaotic sublimation. And the anti-tail itself, pointing sunward, challenges the very definition of a comet, which by nature should release material blown away from the Sun, not toward it.

The broader implication is that we are no longer just documenting anomalies; we are watching consistent behavior that repeats across time, across instruments, and across viewing angles. When a behavior repeats, it becomes evidence. And when evidence repeats across independent platforms—ESA’s Juice spacecraft, Hubble’s pre-perihelion and post-perihelion images, ground-based amateur telescopes—the anomaly is no longer incidental. It is structural.

The timing is crucial because December 19, 2025 marks the close approach of 3I/ATLAS to Earth. That moment will give astronomers their best chance yet to capture high-resolution imaging and spectroscopy before the object moves outward into the colder reaches of the solar system. What we expect to learn on that date is not just the color or shape of the coma, but whether this sunward debris field continues to behave in a coherent pattern as the object cools. Will the anti-tail elongate, or dissipate? Will the nucleus brighten, dim, or rotate? Will the swarm of macroscopic fragments appear more clearly under changing illumination? And most fundamentally, will 3I/ATLAS continue to follow the non-gravitational acceleration profile already measured?

These answers matter because 3I/ATLAS is teaching us, in real time, that interstellar objects do not have to resemble the comets and asteroids we know. They can carry materials we have not yet cataloged. They can react to sunlight in unfamiliar ways. They can shed debris that does not behave like dust. And they can move according to forces our models are only beginning to describe.

Hubble’s newest image confirms that the anomaly was never subtle. It was always there, hiding in plain sight. Now, with December 19 approaching, the world has an opportunity not only to observe it but to understand it. And USA Herald will continue monitoring every frame as new data emerges.