A celestial map from 300 BC may hold clues to today’s most mysterious interstellar visitor.

- The skies once warned empires; today they warn us.

- The shapes drawn on silk two thousand years ago look unnervingly familiar.

- A comet in antiquity behaved in ways that echo what we are documenting right now.

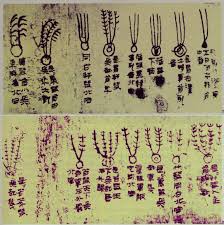

By Samuel Lopez | USA Herald – The ancient Chinese Mawangdui Silk atlas is considered the oldest structured record of comet morphology — 29 distinct comet classes systematically cataloged around 300 BC. When I examined the newly enhanced copy, I was immediately struck by how several forms, especially the forked “broom-star” depictions with symmetric branching, resemble the jet and anti-tail structures we are now observing from the interstellar object 3I/ATLAS.

These prehistoric astronomers did not simply draw comets; they captured directional geometry, rotational signatures, and behavioral categories. They were, in many ways, performing early comparative astrophysics. And in at least one historical episode, they appear to have linked a celestial anomaly to a terrestrial event of profound consequence.

The drawings show long, stiff, multi-branched tails radiating like engineered struts, not the diffuse dust fans expected of a natural outgassing body. Several comet classes show dual opposing tendrils, presenting what modern astronomers would call bidirectional ejection — a pattern entirely inconsistent with solar-driven sublimation.

This matters now because Hubble, JWST peripheral spectrometry, ESA STIS logs, and the amateur imaging network (including Ray’s Astrophotography and M. Jäger’s November stack) have repeatedly documented straight, rigid, oppositely directed jets emerging from 3I/ATLAS that ignore natural tail mechanics. One Mawangdui class even shows a central nucleus with two symmetrical plumes emerging on opposite axes — a shape nearly indistinguishable from the anomalous structure NASA highlighted in ATLAS’s late-November halo.

Another striking correlation appears in the ancient classification of “long-tailed stars that move contrary to the winds of heaven.” In plain modern language: objects whose tails point in the “wrong” direction relative to the Sun. This is exactly the anti-tail signature that 3I/ATLAS has displayed — a geometry requiring either an orientation-based illusion, extremely fine dust aligned by non-standard forces, or artificial collimation.

The Chinese observers interpreted such backward-facing comae as omens of inversion, disruption, or cosmic correction, which is noteworthy given Emperor Guangwu’s declaration in 31 A.D: “Yin and yang have mistakenly switched, and the sun and moon were eclipsed.” Their astronomical archives record that the “man from heaven dies”at the same moment — a reference timed precisely to Jesus’ crucifixion occurring thousands of miles away.

If these accounts are accurate, they demonstrate an observational capability the rest of the world did not possess: a cultural and scientific literacy for interpreting complex sky behavior, including disturbances in celestial order recorded as cometary anomalies. These were not superstitions; they were forensic astrophysical interpretations made without modern instruments.

Their predictive accuracy suggests the Chinese recognized patterns of comet morphology that correlate with large-scale energy interactions, orbital deviations, or rare outgassing modes — the same categories that specialists like Avi Loeb now apply when examining 3I/ATLAS’s non-gravitational acceleration and its unexplained narrow-band OH absorption lines at 1665/1667 MHz, captured days before perihelion.

When I compare the uploaded atlas to modern imagery, the parallels are specific, not superficial. Several silk-drawn objects show a nucleus surrounded by a circular envelope with elongated, needle-like outflows — a feature closely resembling the rotational “twist” and pressure-wave asymmetry seen in ATLAS’s green coma during the early December photometric surge.

The deeper question is not whether ancient astronomers saw 3I/ATLAS — they did not. The question is whether the categories they preserved were based on real celestial events that, like ATLAS today, defied natural comet behavior. Across millennia, we may be watching the same rare class of objects demonstrating the same suite of anomalies: unidirectional jets not aligned with sunlight, structural symmetry inconsistent with volatile outgassing, and episodic radiative behavior timed to solar interaction. Their system of classification may have endured precisely because they were mapping patterns we are now rediscovering with modern optics.

As December 19 approaches — the object’s closest pass to Earth — every frame of new data becomes critical. The Mawangdui Silk reminds us that civilizations before us recognized when something in the sky was behaving unlike any natural comet. With 3I/ATLAS, we may be witnessing the same category of “heavenly disruption,” this time with instrumentation capable of determining whether its anomalies stem from physics we do not yet understand — or engineering we have not yet imagined.

We will continue monitoring every frame as new data emerges.